Borre Style

December 20, 2016

The Anatomy of Viking Art

- Introduction

- Broa Style

- Oseberg Style

- Borre Style

- Jelling Style

- Mammen Style

- Ringerike Style

- Urnes Style

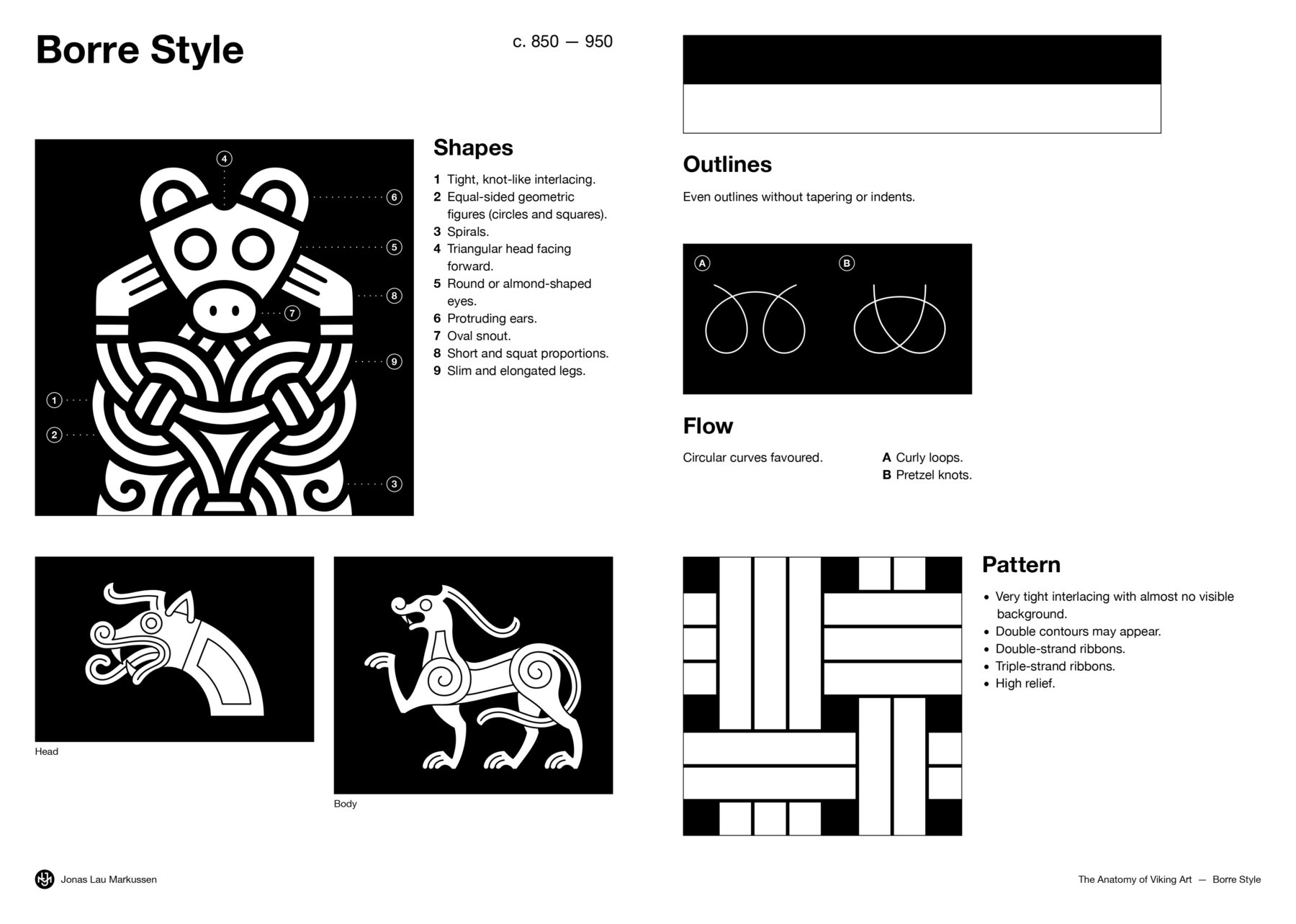

The Anatomy of the Borre Style

c. 850 – 950

Shapes

1. Tight, knot-like interlacing.

2. Equal-sided geometric figures (circles and squares).

3. Spirals.

4. Triangular head facing forward.

5. Round or almond-shaped eyes.

6. Protruding ears.

7. Oval snout.

8. Short and squat proportions.

9. Slim and elongated legs.

Outlines

Even outlines without tapering or indents.

Flow

Circular curves favoured.

A. Curly loops.

B. Pretzel knots.

Pattern

- Very tight interlacing with almost no visible background.

- Double contours may appear.

- Double-strand ribbons.

- Triple-strand ribbons.

- High relief.

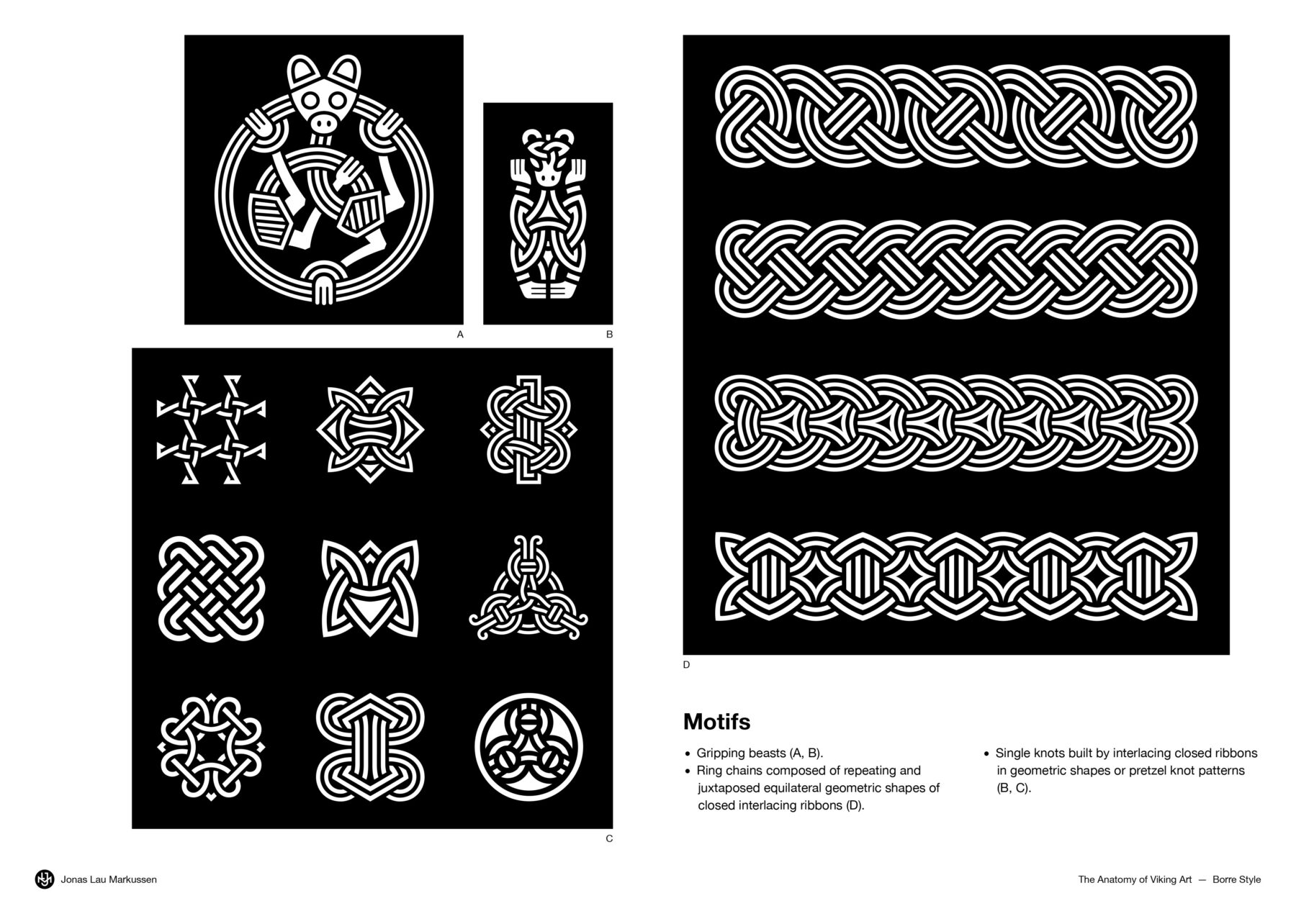

Composition

- Tight compositions of closed ribbons (D), knots (B, C) and animals (A, B).

- Repetition and juxtaposition of geometric shapes (C, D).

Motifs

- Gripping beasts (A, B).

- Ring chains composed of repeating and juxtaposed equilateral geometric shapes of closed interlacing ribbons (D).

- Single knots built by interlacing closed ribbons in geometric shapes or pretzel knot patterns (B, C).

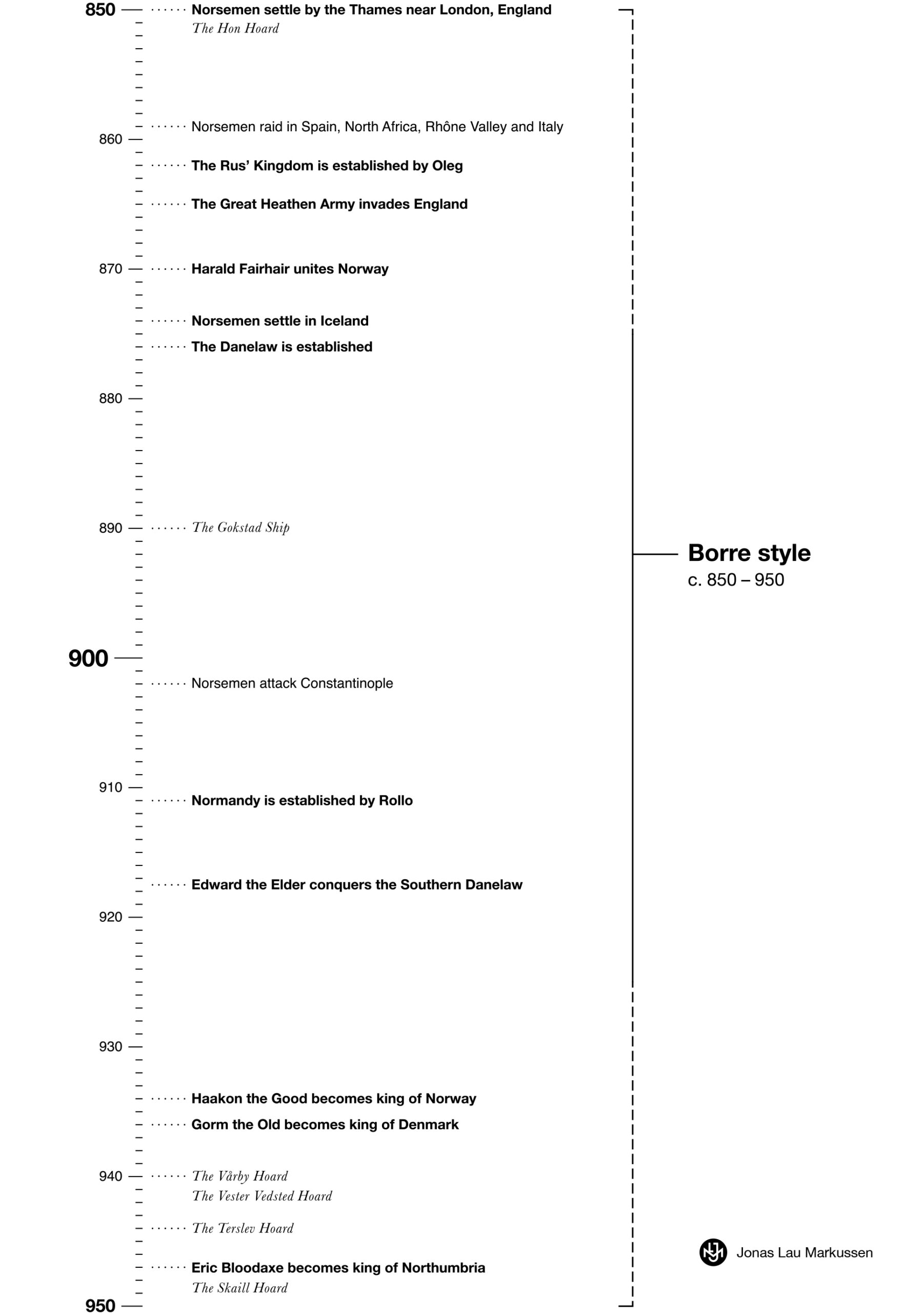

Conquest and Colonisation

Unification of Norway

The Norwegian chieftain, Harald Fairhair, united Norway after his victory in the Battle of Hafrsfjord, and became the first King of Norway. Many of the subjugated petty Norwegian chieftains were dissatisfied with his rule and his taxation of their land, and in their pursuit of freedom, they migrated to other Norse territories.

The Icelandic Commonwealth

The newly discovered island of Iceland was a particularly popular place for the Norwegian emigrants to settle, as there was plenty of fertile land to claim, and soon all the land was acquired by Norse families. To regulate the Icelandic Commonwealth and settle disputes between feuding clans, a legislative and judicial assembly, the All-thing, was formed.

The Danelaw

The coastline of the British Isles had already been raided numerous times when the so-called Great Heathen Army invaded the English Kingdoms. Through a number of military campaigns, allegedly led by Ivar the Boneless, the Norse army was able to first capture the city of York, and then all Northumbria, then Nottingham and Mercia, followed by London and East Anglia. When they encountered the resistance of King Alfred of Wessex, the Norse, now led by Guthrum the Old, had to surrender and sign the treaty that established the boundaries of the Norse territory on the British Isles, known as the Danelaw. Many of the Norse settled permanently in the Danelaw, and in time they became integrated with the original local communities. Norse groups even invaded the territory around Dublin, and established the Norse Kingdom of Dublin.

Normandy

Norse groups continuously raided the coasts of what is today western France, where the treasures at monasteries were guarded only by monks, who were easy prey. The Norse eventually travelled up the Seine, reaching Paris, spreading terror on their way. To put an end to the Norse assaults, the French King Charles the Simple gave the Norse chieftain, Rollo, Upper Normandy in exchange for Norse allegiance and protection against further Norse raids, and conversion to Christianity by baptism. In reality, this established Normandy as a Norse colony under French rule, though the Norman dukes were practically independent of the French king.

The Rus’ Kingdom

In Eastern Europe, the Rus’ settlements were now well-established. Oleg, a relative of Rurik, seized power over Kiev from his own brother, and in doing this, established what would become the kingdom of the Kievan Rus’, ruled by the Rurik dynasty. From his new position in Kiev, which controlled the Slavic areas’ trade routes, Oleg was able to launch at least one attack on the wealthy capital of the Byzantine Empire, Constantinople. At the same time, the Byzantine emperor began to recruit elite Norse warriors exclusively, to serve as his personal guard, known as the Varangian Guard, to protect him from political attacks from within the Empire.

Golden Age of the Gripping Beast

Development

If the Oseberg style saw innovation in, and a reimagination of the traditional Norse animal ornament, the Borre style represents a further, almost complete departure in many ways. While the traditional gripping beast took centre stage and became the principal animal form of the Borre style, the ribbon animal vanished almost entirely for the first time in Germanic and Norse tradition. Though we often do find the typical ribbon animal head in profile, with its neck tendril, it is mostly used as just a ribbon terminal or decorative afterthought. Instead of intertwining ribbon animals, the interlacing patterns were now often almost exclusively geometric. These framework patterns may have originated in a further development of the geometric framework of the preceding Broa and Oseberg styles. The spiral was among the new geometric features introduced, probably inspired by European vegetal scroll motifs, though often used to represent animal hip joints. The gripping beast was often used either in its entirety as a centrepiece of the composition, curled up in a pretzel-like knot, or appeared simply as a single head applied to the end of a ribbon in an interlacing pattern, such as the ring-chain ornament. The gripping beast often also appears with just a knot for its body, with ribbon terminals in the shape of the head and paws.

Dating

The Borre style is the first phase of Viking Age art that may be more accurately dated, based on a few coin finds in conjunction with metalwork in hoards.

Gripping Beast Pendants

Some of the most iconic Borre-style pieces are the pendants found across Scandinavia, which display a typical gripping beast with its ribbon body and squat, wide hips, curled up in a pretzel knot, gripping its own slender limbs and the surrounding circular frame with its four paws.

The Borre Harness Mounts

On the horse-harness mounts from a ship grave in Borre, from which this style got its name, we find the other trademark of the Borre style, the so-called ring chain. This is formed by juxtaposing geometric shapes, typically circles and rhombuses, which often terminate in the triangular head of a gripping beast. The ring-chain pattern schemes are not known from Scandinavian tradition or foreign models, and therefore may be a Scandinavian innovation. A variation of the ring chain, Gaut’s ring chain, was widely used in the Norse regions of the British Isles, and is seen on many stone crosses, the most notable of which are those made by Gaut Bjørnson.

The Birka Penannular Brooch

The penannular brooch from Birka is an excellent example of a combination of all the Borre style characteristics. Ring chains, knots, gripping beast heads and even tiny heads of ribbon animals are all part of the composition.

Distribution

The expansion and new settlements of the Norse are well-reflected in the distribution of Borre-style artefacts. The style is also the earliest to be found outside of Scandinavia. Not only do we find items made by the Norse in the Borre style, but the style also influenced the local styles of the settled regions, and the style itself represents a stage of decorative eclecticism. The style was especially popular in the British Isles, where it was picked up and combined with local trends. Although stone carving was virtually non-existent in Scandinavia, it was very common in the British Isles, and local artists integrated the Borre style in many works in stone.

Examples

Examples on Gelmir.com →

A list of examples with photos, info and links to sources.

Dateable

c. 890 (the ship)

Belt mounts — the Gokstad Grave

Gokstad, Vestfold, Norway.

Kulturhistorisk Museum, Oslo, C10441.

c. 890 (the ship)

Animal-head bedpost — the Gokstad Grave

Gokstad, Vestfold, Norway.

Kulturhistorisk Museum, Oslo C10408.

c. 940 (youngest coin)

Gripping beast pendants — the Vårby Hoard

Vårby, Södermanland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 106692.

Undateable

Bit *

Gotland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 459127.

Brooch/mount — Romerike *

Romerike, Akershus, Norway.

Kulturhistorisk Museum, Oslo, C4640.

Gaming board

Gokstad, Vestfold, Norway.

Kulturhistorisk Museum, Oslo, C10406.

Gripping beast pendant — Little Snoring *

Little Snoring, Norfolk, England.

The British Museum, London, 1999,1001.1.

Gripping beast pendants — Träslöv *

Träslöv, Halland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 867721; 867724.

Horse harness bow — Björkö *

Björkö, Uppland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 107781.

Horse harness bow — Tunby *

Tunby, Västmanland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 266711.

Horse-harness mounts — the Borre Grave

Borre, Vestfold, Norway.

Kulturhistorisk Museum, Oslo, C1804.

Quatrefoil brooch — Rinkaby

Rinkaby, Skåne, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 107277.

Round brooch — Bjølstad *

Bjølstad, Innlandet, Norway.

Kulturhistorisk Museum, Oslo, C23005.

Round brooch — Björkö *

Björkö, Uppland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 416194.

Round brooch — Björkö *

Björkö, Uppland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 480116.

Round brooch — Björkö *

Björkö, Uppland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 609746.

Strap end, strap mount and spur — Rød hoard

Rød, Viken, Norway.

Kulturhistorisk Museum, Oslo, C22406; C5905; C5906.

Strap end and belt buckles — Duesminde hoard *

Duesminde, Lolland, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, C35316-94.

Strap end — Var Store *

Var Store, Vestfold, Norway.

Kulturhistorisk Museum, Oslo, C14296.

Penannular brooch — Ala *

Ala, Gotland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 448544.

Penannular brooch — Alkvie *

Alkvie, Gotland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 448473.

Penannular Brooch — Björkö *

Björkö, Uppland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 40460.

Penannular Brooch — Björkö *

Björkö, Uppland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 108812.

Penannular Brooch — Björkö *

Björkö, Uppland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 122924.

Penannular brooch — Björkö *

Björkö, Uppland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 444244.

Penannular Brooch — Björkö *

Björkö, Uppland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 471280.

Penannular brooch — Ferkingstad *

Ferkingstad, Rogaland, Norway.

Arkeologisk Museum Universitetet i Stavanger, Stavanger, S1052.

Penannular brooch — Kråkberg *

Kråkberg, Dalarna, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 444244.

Penannular brooch — Spissøyno *

Spissøyno Nedre, Vestland, Norway.

Universitetsmuseet i Bergen, Bergen, B11377.

Penannular brooch — Tomta *

Tomta, Gotland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 416462.

Penannular brooch — Valva *

Valva, Gotland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 416461.

Pin *

Sojvide, Gotland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 120508.

Tiller *

Gokstad, Vestfold, Norway.

Kulturhistorisk Museum, Oslo, C10391.

Three-dimensional brooch — Gotland

Gotland, Sweden.

The British Museum, London, 1901,0718.1.

Trefoil brooch — Blakar *

Blakar, Innlandet, Norway.

Kulturhistorisk Museum, Oslo, C6743.

Trefoil brooch — Holmskov *

Holmskov, Als, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, C8964.

Trefoil brooch — Ladby *

Ladby, Fyn, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, C23037.

Trefoil brooch — Lunnäs *

Lunnäs, Värmland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 781351.

Trefoil brooch — Norway *

Norway.

Kulturhistorisk Museum, Oslo, C4730.

Trefoil brooch — Revheim *

Revheim, Rogaland, Norway.

Arkeologisk Museum Universitetet i Stavanger, Stavanger, S1656.

* Examples added to the list in 2023.

Examples removed from the list in 2023

- Animal-head needle. Hedeby, Schleswig, Germany. Archäologisches Landesmuseum Schleswig, Schleswig.

- Bridle. Suputry, Rusland.Gosudarstvennui Istoricheskii Muzei, Moskva.

- Bronze dies. Hedeby, Schleswig, Germany. Archäologisches Landesmuseum Schleswig, Schleswig.

- Equal-armed brooch. Elec, Upper Don, Russia. Gosudarstvennyj Ermitaž, Saint Petersburg 997/1.

- Gaut’s Cross. Kirk Michael, Isle of Man.

- The Hiddensee Hoard. Hiddensee, Rügen, Germany. Kulturhistorisches Museum Stralsund 1873: a–d, f–g, i, 450. 1874: 39 a–b, 91–92, 162,176.

- Ship and gripping beast ornament. Randlev, Jutland, Denmark. Nationalmuseet, Copenhagen.

Reclassified in 2023

- Animal head pendant. Sigtuna, Uppland, Sverige. Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 44065. → Jelling Style.

- Cruciform pattern filigree disc brooch. Finkarby, Taxinge, Södermanland, Sweden. Historiska Museet, Stockholm. → Jelling Style.

- Terslev style pendant. Hedeby, Schleswig, Germany. Archäologisches Landesmuseum Schleswig, Schleswig. → Jelling Style.

Litterature

Graham-Campbell, James, 2013. Viking Art.

Fuglesang, Signe Horn, 1982. ‘Early Viking Art.’ Acta ad Archaeologiam et Artium Historiam Pertinentia (Series altera in 8°) 125–173.