Mammen style

December 20, 2016

The Anatomy of Viking Art

- Introduction

- Broa Style

- Oseberg Style

- Borre Style

- Jelling Style

- Mammen Style

- Ringerike Style

- Urnes Style

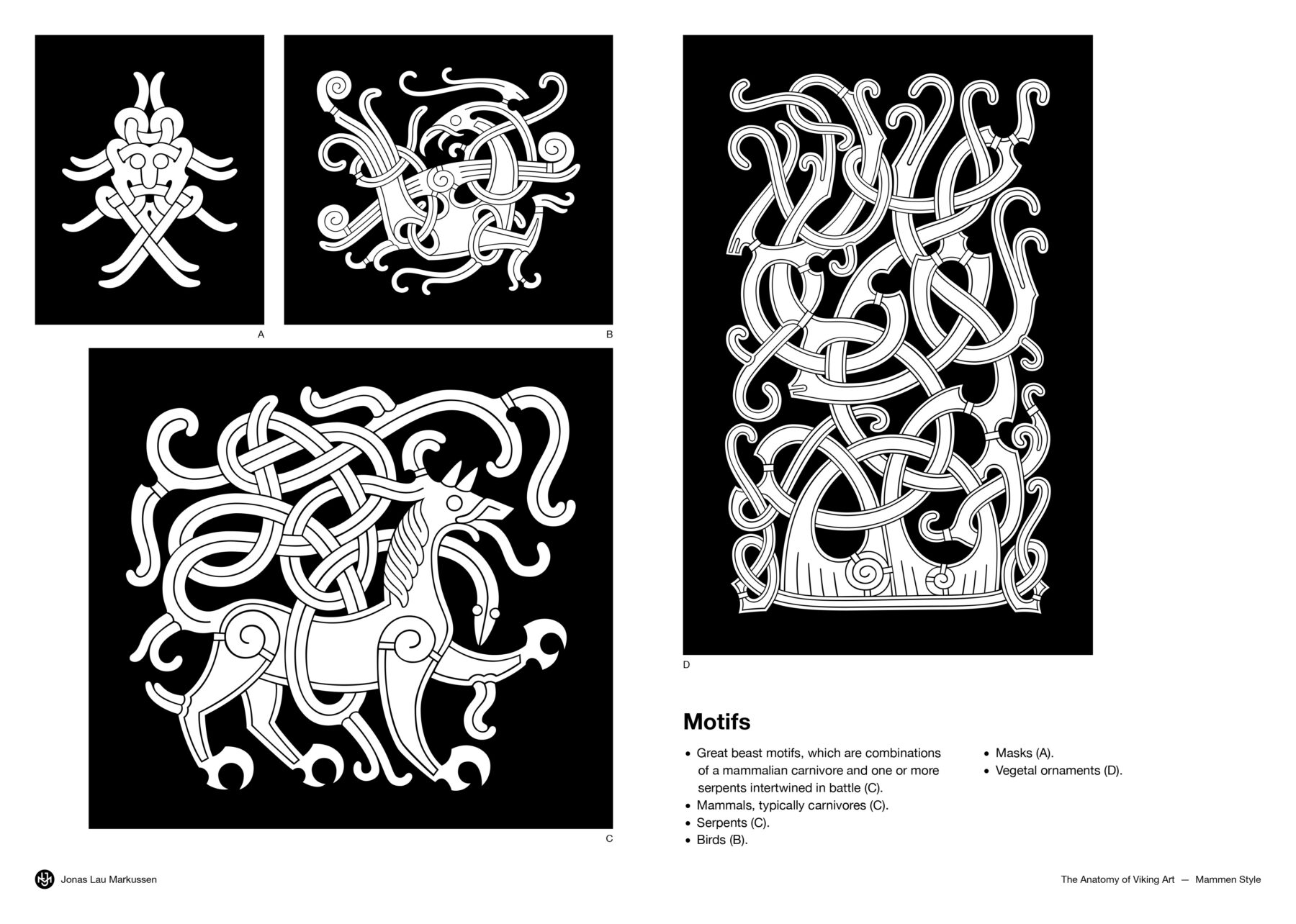

The Anatomy of the Mammen Style

c. 950 – 1025

Shapes

1. Long and wavy S-shaped tendrils.

2. Loosely scrolled tendril terminals.

3. Spirals as tendril terminals.

4. Pellets intersecting ribbons.

5. Concave indents.

6. Head in profile.

7. Round or almond-shaped eye.

8. Spiral hip joints.

Outlines

Curvy outlines with kinks and frequent indents.

Flow

Flowing loose and wavy curves.

A. Curly loops.

B. Pretzel knots.

C. S-shapes.

Pattern

- Semi-open interlacing with some visible background.

- Double contour.

- Single-strand ribbons.

- Double-strand ribbons.

Composition

- Single motifs (A, B, C).

- Loosely flowing compositions without axes and symmetry (B, C, D).

- Additive principles.

- Stem and tendril ribbons often have the same width.

Motifs

- Great beast motifs, which are combinations of a mammalian carnivore and one or more serpents intertwined in battle (C).

- Mammals, typically carnivores (C).

- Serpents (C).

- Birds (B).

- Masks (A).

- Vegetal ornaments (D).

Christianisation of the Norse

The Conversion of Denmark

When Gorm the Old died, his son, Harald Bluetooth, became king of Denmark and acquired power over Norway a few years later. The joint ruler of the empire just south of the Dannevirke, Otto II, was keen on Christianising the Norse regions, by a violent military crusade if necessary. This threat forced Harald to convert, and to make Christianity Denmark’s new religion. To communicate this point, he erected the Greater Jelling Stone, with its runic inscription that states that Harald united all Denmark, and converted the Danes. To further secure his status and control of the kingdom, he built a number of ring fortresses throughout the territory of Denmark, and fortified the Jelling monument site, the royal centre of power. Harald’s display of power may have prevented Otto II from conquering Denmark, but after his father, Otto the Great, died, making him the sole ruler, he captured Hedeby, which was a tremendous blow to Harald. Otto II then suddenly died, and as his three-year-old son was the only legitimate heir, this left the empire in a state of complete political crisis. This led to Harald regaining control over Hedeby that same year. However, Harald’s victory was short-lived, as he was then killed by his son, Sweyn Forkbeard, who took control of the kingdom.

The Conversion of the Rus’

After a period of exile in Sweden, Vladimir the Great of the Rurik dynasty returned to Novgorod with a Varangian army, took back control of the Rus’ Kingdom from his brother, and soon after consolidated his rule of a sizeable Kievan territory. He was baptised, and Christianised all the Kievan Rus’.

The Conversion of Norway and Iceland

The heir to the Norwegian throne, Olaf Tryggvason, who was chief of Vladimir’s men-at-arms while exiled from Norway, joined forces with Sweyn Forkbeard to lead an attack on England with a fleet of 90 ships, and collected the first Danegeld. They later returned to collect the second Danegeld, and as part of the treaty with King Æthelred the Unready, Olaf was baptised. After his success in England, Olaf returned to Scandinavia, successfully claimed the Norwegian throne and converted the Norwegians to Christianity. Iceland followed suit a few years later, through a somewhat democratic decision at the All-thing, mainly due to its dependence on trade connections with Norway. Olaf Tryggvason later fell foul of Sweyn Forkbeard by marrying Sweyn’s already-married sister, Sigrid the Haughty. Sweyn then defeated Olaf in the Battle of Svolder with the support of Erik Jarl – who then became king of Norway – and Olof Skötkonung, who was the first Christian king of a united Sweden.

Colonisation of Greenland and Vinland

After all the inhabitable land in Iceland had been settled, Erik the Red established the first Norse colony on Greenland. His son Leif Eriksson (also known as Leif the Lucky) later discovered North America by accident, and attempted to colonise the land, which he called Vinland, but the settlement was ultimately a short and futile endeavour.

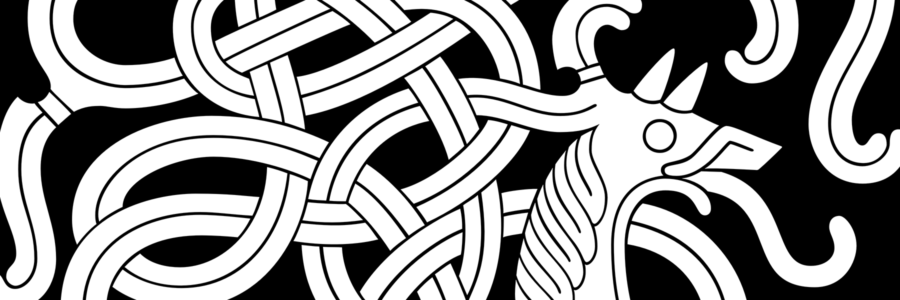

The Great Beast is Born

Development

The animals of the Mammen style are a stylistic continuation of the Jelling-style ribbon animal, though now with a more elaborate and often more naturalistic execution. The style was further inspired by Continental European influences, which may be seen in the introduction of more vegetal elements, such as vines, lobes and spirals. The interlacing patterns are developed in a less geometric, wavier and more flowing manner, reminiscent of vines.

Dating

The Christianisation of Scandinavia changed Norse burial customs. After the conversion, the dead were buried with very few artefacts, owing to the new religious beliefs, which rejected the importance of material goods accompanying the dead into the afterlife. The archaeological evidence comes mostly from the few hoards that may have been buried for safekeeping in times of conflict. Too few objects have been found in datable contexts to permit anything other than approximate dating.

The Greater Jelling Stone

The best-known example of the Mammen style is the Greater Jelling Stone, raised by Harald Bluetooth. On one of its three sides, we see for the first time the motif of the great beast, which came to be the most influential and widely used motif throughout the rest of the Viking Age. The motif consists of a large, four-legged animal, reminiscent of a lion or wolf, and a serpent, intertwined in battle. The motif builds heavily on Scandinavian artistic traditions while incorporating European influences. Therefore, it is difficult to determine the exact meaning of this image, but it may have been a symbol of royal or religious power, and may very well have been inspired by similar designs used in aristocratic environments in Continental Europe and the British Isles. On one of the other three sides of the stone we see a clear depiction of Christ, which was a highly untraditional motif in Scandinavia until then, though executed in an entirely traditional Norse style. The Greater Jelling Stone inspired copies throughout the Norse regions. However, the copies typically include only the great beast, and omit the image of Christ.

The Mammen Axe

The Mammen style got its name from the decorated axe head found among the rich grave goods of an aristocrat connected to the Jelling dynasty, buried just after the conversion of Denmark. One side is covered with a composition of waving foliate tendrils, and a bird in the same style occupies the other side.

The Bamberg and Cammin Caskets

Two of the most elaborate Mammen-style works are the casket from the Bamberg Cathedral, Germany, and the casket from the cathedral of Kamień Pomorski, Poland. Unfortunately, the latter was destroyed during World War II, though exact copies still exist. The Cammin casket is an excellent example of the integration of Norse artistic traditions and Christian iconography. Symbolic representations of the four evangelists appear on the lid and sides of the casket. John is represented by eagles, Luke by bulls depicted as four-legged animals with hooves, Matthew by a human mask and Mark by lions with clawed paws. Originally, the shrine may have contained a gospel or liturgical manuscript. Religious gifts of this kind played an essential role in the establishment of relationships between European and Norse rulers, and of generous donations to the Church.

Distribution

The Mammen style was widely popular throughout Scandinavia and the settled areas of Europe, especially the British Isles.

Examples

Examples on Gelmir.com →

A list of examples with photos, info and links to sources.

Dateable

c. 958 – 959

Wood carvings — the Jelling North Mound

Jelling, Jylland, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København CCCLXXV-.

c. 965 – 975

Jelling Runestone DR 42

Jelling, Jylland, Denmark.

c. 970 – 971

Axe head — the Mammen Grave

Mammen, Jylland, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, C133.

Undateable

Cylinder — Årnes

Årnes, Møre og Romsdal, Norway.

NTNU Vitenskapsmuseet, Trondheim, T18308.

Cylinder — Aa med Auset *

Aa med Auset, Trøndelag, Norway.

NTNU Vitenskapsmuseet, Trondheim, T19027.

Fragment *

Reistad, Trøndelag, Norway.

NTNU Vitenskapsmuseet, Trondheim, T15137.

Handle

Køge, Sjælland, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, C18000.

Plaque

Thames, London, England.

The British Museum, London, 1866,0224.1.

Reliquary Shrine — Bamberg

Bamberger Dom, Bayern, Germany.

Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, München, MA 286.

Reliquary Shrine — Kamień

Konkatedra św. Jana Chrzciciela, Kamień Pomorski, Poland.

Now lost.

Reliquary Shrine — Léon

Basílica de San Isidoro, León, Spain.

Basílica de San Isidoro, León, SP 27-1-11A4.

Runestone DR 66

Aarhus, Jylland, Denmark.

Moesgaard Museum, Højbjerg.

Spear

Nomeland, Agder, Norway. *

Universitetsmuseet i Bergen, Bergen, B5207/e.

Sword — Hedmark *

Hedmark, Norway.

Kulturhistorisk Museum, Oslo, C257.

Sword — Sandbu *

Sandbu, Innlandet, Norway.

Kulturhistorisk Museum, Oslo, C237.

Sword — Gjermundbu *

Gjermbu, Gjermundbu, Viken, Norway.

Kulturhistorisk Museum, Oslo, C27317.

Sword — Århus *

Århus, Fyresdal, Vestfold og Telemark, Norway.

Kulturhistorisk Museum, Oslo, C39278.

Sword — Vold *

Vold, Innlandet, Norway.

Kulturhistorisk Museum, Oslo, C15888.

Sword Pommel — Sigtuna

Sigtuna, Uppsala, Sweden.

Sigtuna Museum & Art, Sigtuna, SF 1965.

Sword Pommel — Gråsand *

Gråsand, Jylland, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, Dnf. 25/04.

* Examples added to the list in 2023.

Examples removed from the list in 2023

- Gilt bronze plate. Aarhus, Jylland, Denmark. Aarhus Museum, Aarhus.

- Odd’s Cross. Kirk Braddan, Isle of Man.

- Thorleif’s Cross. Kirk Braddan, Isle of Man.

Litterature

Graham-Campbell, James, 2013. Viking Art.

Fuglesang, Signe Horn, 1980. Some Aspects of the Ringerike Style.

Fuglesang, Signe Horn, 1981. ‘Stylistic Groups in Late Viking and Early Romanesque Art.’ Acta ad Archaeologiam et Artium Historiam Pertinentia (Series altera in 8°) 79–125.

Jörn Stäecker, 2006. Decoding Viking art, The Christian iconography of the Bamberg Shrine.