Oseberg Style

December 20, 2016

The Anatomy of Viking Art

- Introduction

- Broa Style

- Oseberg Style

- Borre Style

- Jelling Style

- Mammen Style

- Ringerike Style

- Urnes Style

The Anatomy of the Oseberg Style

c. 800 – 875

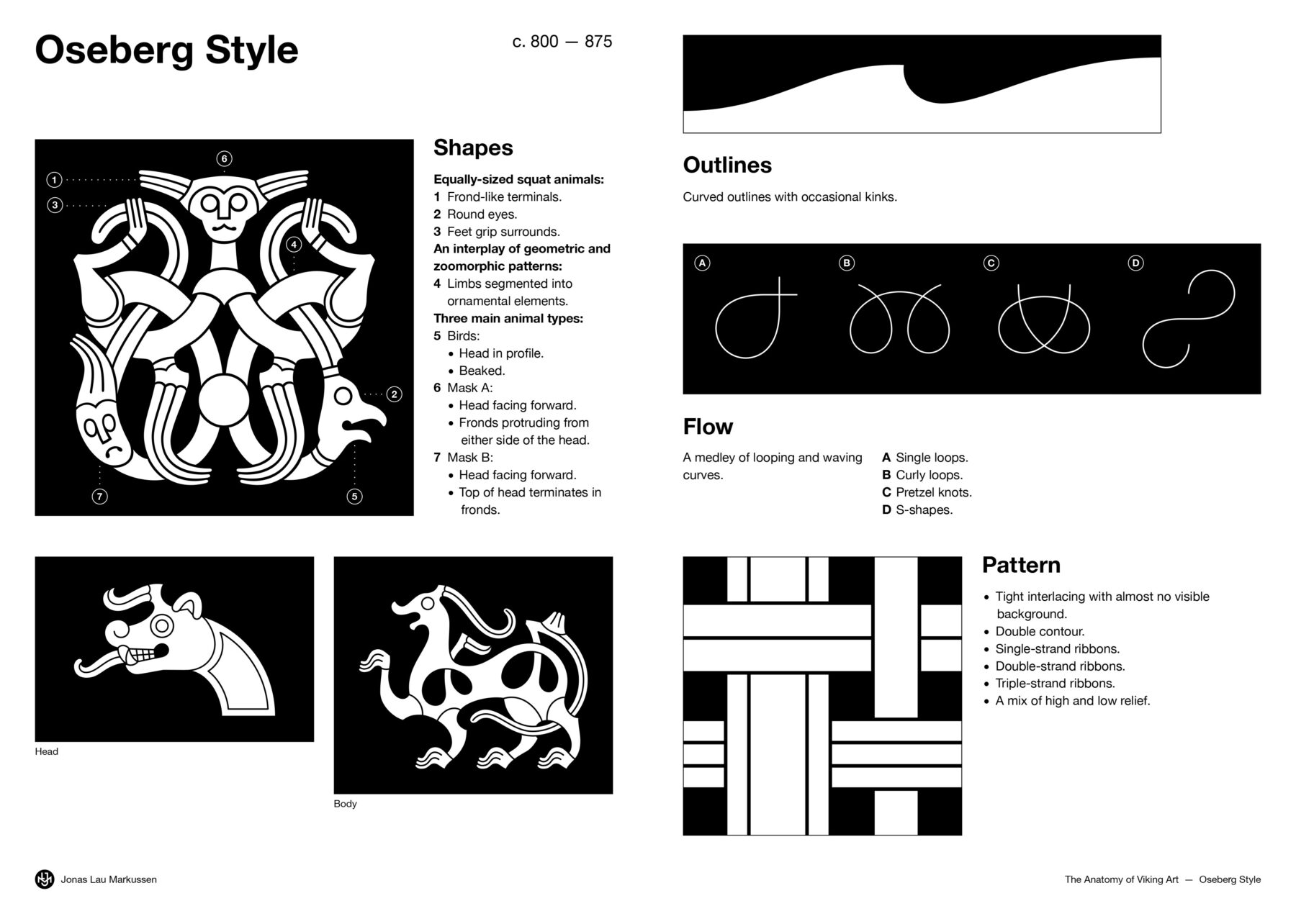

Shapes

Equally-sized squat animals:

1. Frond-like terminals.

2. Round eyes.

3. Feet grip surrounds.

An interplay of geometric and zoomorphic patterns:

4. Limbs segmented into ornamental elements.

Three main animal types:

5. Birds:

– Head in profile.

– Beaked.

6. Mask A:

– Head facing forward.

– Fronds protruding from either side of the head.

7. Mask B:

– Head facing forward.

– Top of head terminates in fronds.

Outlines

Curved outlines with occasional kinks.

Flow

A medley of looping and waving curves.

A. Single loops.

B. Curly loops.

C. Pretzel knots.

D. S-shapes.

Pattern

- Tight interlacing with almost no visible background.

- Double contour.

- Single-strand ribbons.

- Double-strand ribbons.

- Triple-strand ribbons.

- A mix of high and low relief.

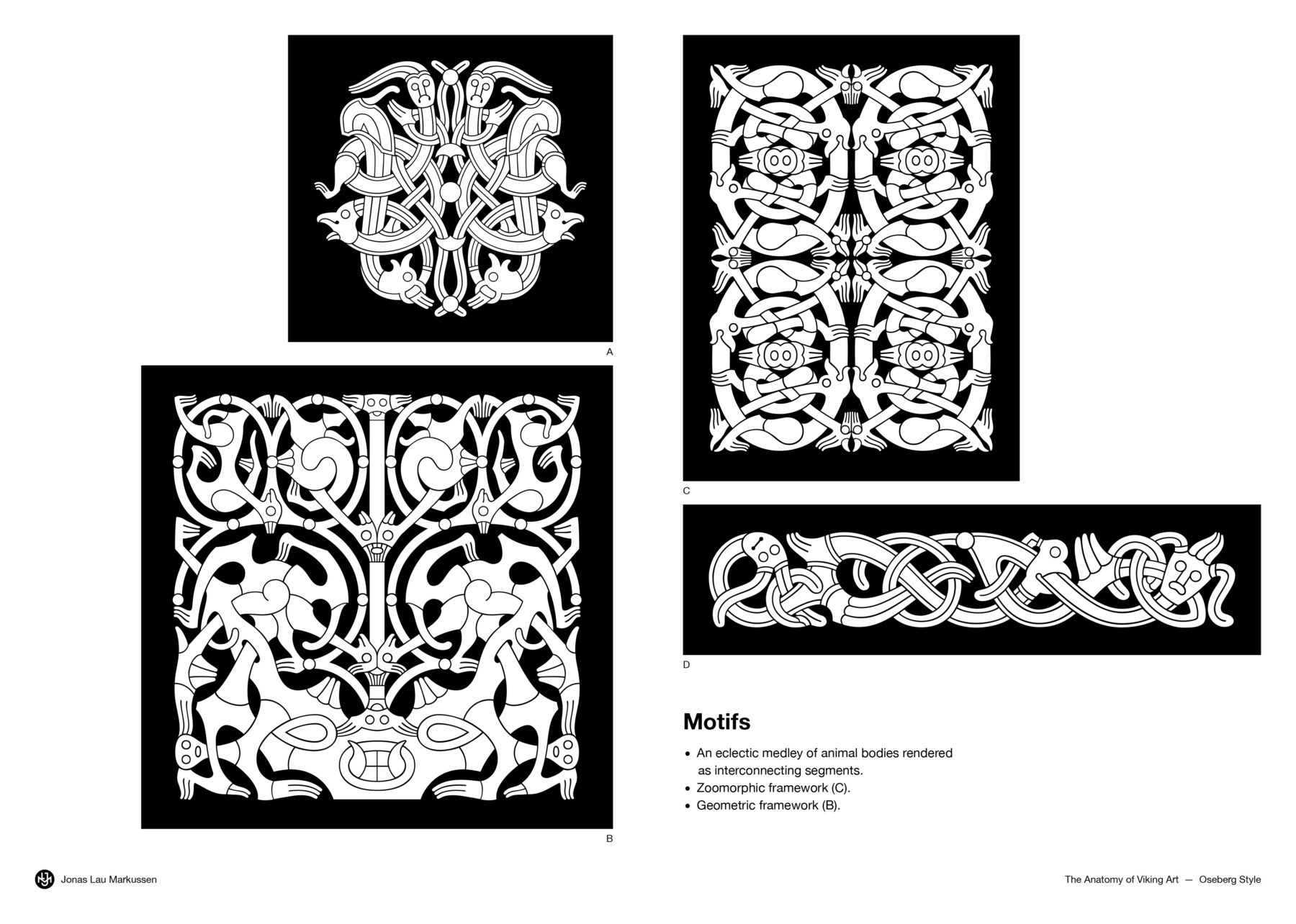

Composition

- An absence of main compositional lines (A, D).

- Carpet-like distribution of motifs of equal size and equal compositional value.

- Geometric and zoomorphic framework, oval or rhomboid (B, C).

- Apparent symmetry in the composition; however, differences in detail (A, B, C).

Motifs

- An eclectic medley of animal bodies rendered as interconnecting segments.

- Zoomorphic framework (C).

- Geometric framework (B).

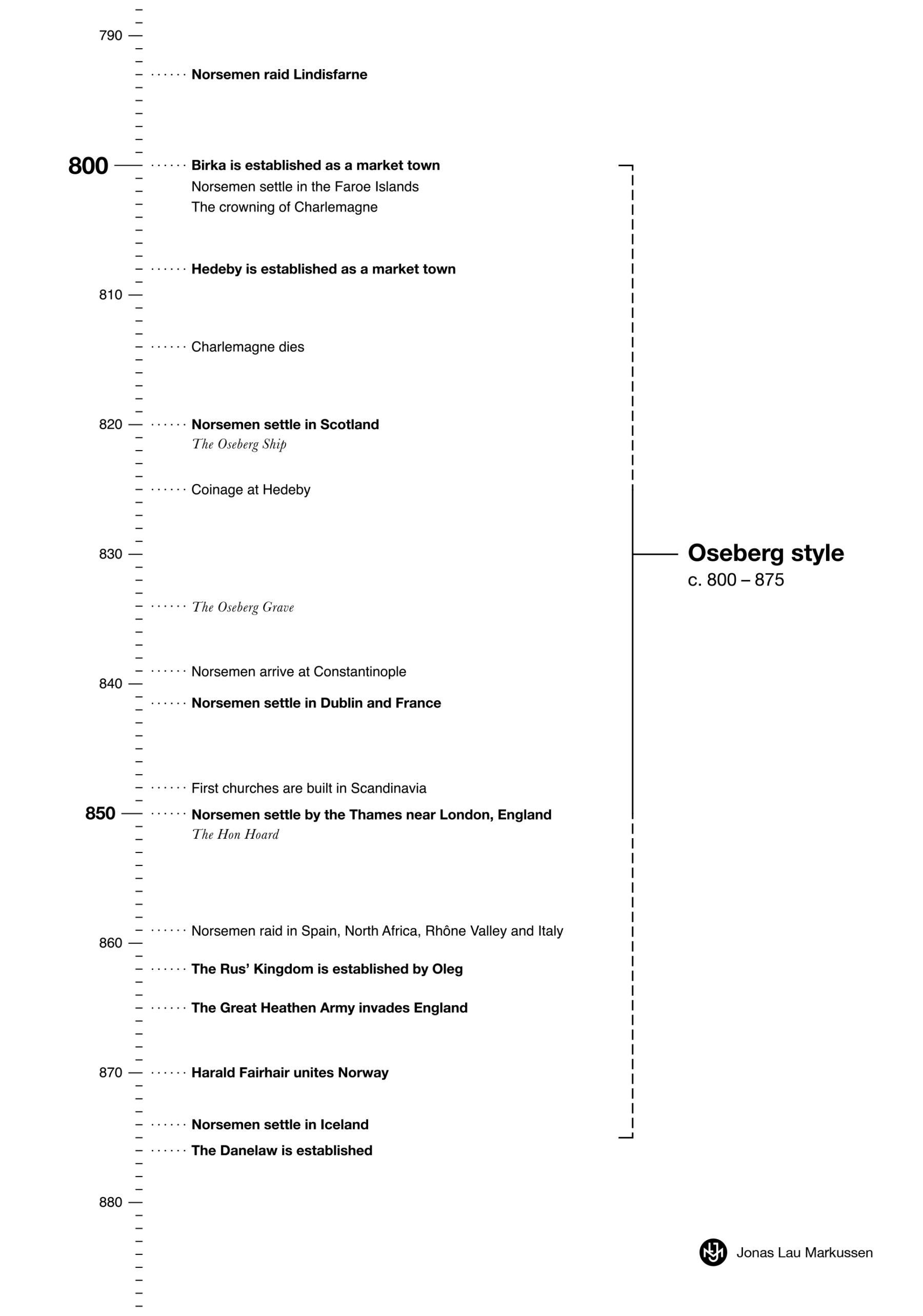

Exchange and Early Expansion

Trade and Raids

The spirit of the Norse expeditions and their exchanges with the communities of the surrounding European regions was mostly opportunistic. Whether these were for trade, raid or settlement depended on the individual circumstances. Several Norse trading towns were well-established along the popular trading routes. They were centres of fluctuating cosmopolitan influences and material goods, and manifestations of all the connections with the various European tribes and societies through the far-reaching trading routes, overseas and along the continental rivers. These towns soon became powerful cultural hubs at several levels: economic, military, social, religious and artistic. Therefore, for the local rulers that collected taxes and controlled who and what entered and left the territory, control over these places was crucial.

The Eastern Routes

The Swedish trading town of Birka was the gateway to Eastern Europe. From here, all the Slavic regions could be reached by the rivers from the Baltic Sea, such as the Volga and Dnieper, eventually reaching Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire. The Norse, or the Rus’ as they were known in Eastern Europe, came from what is today Roslagen, the coastal areas of Uppland in modern-day Sweden, and settled along the northern parts of these routes, to make the journeys more convenient and to be better able to trade with and raid the local Slavic tribes. The Rus’ chieftain, Rurik, gained control of the Ladoga trading post, and later established a settlement further south, at Novgorod.

The Western Routes

Hedeby, situated at the southern border of Scandinavia, was the gateway to Western and Central Continental Europe. Bordering the mighty Catholic Frankish Empire to the south, and connected with the British Isles to the west through the Baltic Sea, and the rest of Scandinavia to the east through the North Sea, Hedeby was a crossroads for religious, monetary and cultural influences. Continual traffic in material goods flowed through the town. The Orkney, Shetland and Faroe Islands were settled by Norse emigrants who saw an opportunity in moving their households to these almost uninhabited and fertile islands, and making a new life. The islands soon became a bridgehead for further expeditions to, and raids on Scotland and the rest of the British Isles. The Frankish emperor, Louis the Pius, appointed Bishop Ansgar as missionary to the northern lands, and in turn, the Norse rulers allowed him to build churches in some of the most important trading towns. But as the Frankish Empire crumbled, the power, need or incentive to force the Christian faith on the ‘barbarians’ of the North lacked the support it needed to be successful, and as most of the Norse people saw no reason to convert, the first attempts at Christianising the North were largely futile.

A Remix of Conventions

Development

It is difficult to pinpoint and document what the style between the Broa and Borre styles may have looked like, and various theories have been proposed. This guide presents a type of style primarily represented by the Oseberg ship-grave, which has been dendrochronologically dated to a period between the Broa and the Borre styles. The Oseberg burial mound features some magnificent woodwork, comprising sledges, wagons, a ship, tent poles and more. Among the artefacts are some artworks done in an unmistakably Broa style. In conjunction with this, there are also many works that do not seem to fit the Broa style proper. Although they seem to feature many of the same characteristics, they also consistently and radically differ in many distinct ways. It seems that these works may represent a development of the Broa style in a new direction, which in some ways suggests the Borre style. For instance, the ribbon-like animals clearly refer back to the elegant and abstract ribbon animals of the Broa style, whereas the emphasis on the squatter shapes of the animals and the way they now consistently grasp each other and the surrounding frames suggest the application of the gripping beast of the Borre style. Even the mix of heads in profile, typical of the Broa style, and forward-facing heads, typical of the Borre style, suggests that this style represents a possible transition between the two styles. The Oseberg style is a clear development of the Norse traditions, and has no traceable influences from outside of Scandinavia. The style generally features a more relaxed and unconventional take on animal ornament. Traditionally, the individual animal of the ornament interlacing would always be depicted as a clear but extremely abstracted representation of a single, somewhat anatomically correct animal, typically with one head, one body, two or four legs and a tail. However, in the Oseberg style there is often no distinction among the individual animals in the ornament. Animal limbs and bodies are all thrown together in an eclectic mix to create the liveliest multilevel intertwining ornaments possible. Even the Broa style conventions of clearly distinguishing among, and separating the ribbon animals and the gripping beasts seem completely disregarded, as the features of each are typically merged together.

The Sledge Poles

The two sledge poles display a geometric framework similar to the Broa style, but the execution of the animals departs from it. They are mostly single and whole animals, but they occasionally blend together to fit the structure of the ornamental lines and framework.

The Baroque Animal-head Posts

On the two Baroque animal-head posts, the seemingly geometric framework is actually created entirely of the animals’ limbs, disregarding the individual animals completely, and separating their body parts into mere ornamental segments to produce a composition abundant in ornate elements.

The Fourth Sledge and Gustafson’s Sledge

On Gustafson’s Sledge and the Fourth Sledge, we see the mixed and merged animal ornament in a more free-flowing composition of elements, without any apparent intention of imitating a geometric framework.

Distribution

The Oseberg style, like the Broa style, is unknown outside of Scandinavia, which suggests that the style had developed into the succeeding Borre style before the expansion of the Norse world into more permanent settlements in regions outside of Scandinavia.

Examples

Examples on Gelmir.com →

A list of examples with photos, info and links to sources.

Dateable

c. 820

The ship — the Oseberg Grave

Oseberg, Vestfold, Norway.

Universitetets Oldsakssamling, Oslo C55000/1, C55000/2.1, C55000/31, C55000/35, C55000/106.

c. 834

The Baroque Animal-head Post — the Oseberg Grave

Oseberg, Vestfold, Norway.

Kulturhistorisk Museum, Oslo, C55000/123.

c. 834

Bed — the Oseberg Grave *

Oseberg, Vestfold, Norway.

Kulturhistorisk Museum, Oslo, C55000/113, C55000/114.I.

c. 834

The Big Bed — the Oseberg Grave

Oseberg, Vestfold, Norway.

Kulturhistorisk Museum, Oslo, 55000/187.

c. 834

The Finest Sledge Pole — the Oseberg Grave

Oseberg, Vestfold, Norway.

Kulturhistorisk Museum, Oslo, C55000/17.

c. 834

The Intact Sledge Pole — the Oseberg Grave

Oseberg, Vestfold, Norway.

Kulturhistorisk Museum, Oslo, C55000/196.

c. 834

The Carolingian Animal-head Post — the Oseberg Grave

Oseberg, Vestfold, Norway.

Kulturhistorisk Museum, Oslo, C55000/173.

c. 834

The Fourth Sledge — the Oseberg Grave

Oseberg, Vestfold, Norway.

Kulturhistorisk Museum, Oslo C55000/208.

c. 834

Gustafson’s Sledge — the Oseberg Grave *

Oseberg, Vestfold, Norway.

Kulturhistorisk Museum, Oslo, C55000/179.

c. 834

Shetelig’s Sledge — the Oseberg Grave

Oseberg, Vestfold, Norway.

Kulturhistorisk Museum, Oslo, C55000/195.

c. 850

Pendant — the Hon Hoard

Hon, Viken, Norway.

Kulturhistorisk Museum, Oslo, C747 (The hoard: C719-51).

Undateable

Brooch — Hesselholm *

Hesselholm, Sjælland, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, C24363.

Brooch — Törnbotten *

Törnbotten, Öland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 1322165.

Equal-armed brooch — Björkö *

Björkö, Uppland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 547494.

Equal-armed brooch — Markestad *

Markestad, Innlandet, Norway.

Kulturhistorisk Museum, Oslo, C18594.

Equal-armed brooch — Stronglandshals *

Stronglandshals, Troms, Norway.

UiT Norges Arktiske Universitetsmuseum, Tromsø, Ts47.

Oval brooch — Björkö *

Björkö, Uppland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 529520.

Oval brooch — Lisbjerg *

Lisbjerg, Jylland, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, C11331.

Oval brooch — Gerlev-Dråby *

Gerlev-Dråby, Sjælland, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, C28534; C28535.

Oval brooch — Gutdalen *

Gutdalen, Vestland, Norway.

Universitetsmuseet i Bergen, Bergen, B5030/a.

Oval brooch — Hov *

Hov, Nordland, Norway.

Kulturhistorisk Museum, Oslo, B1027.

Oval brooch — Tissø *

Tissø, Sjælland, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, C5370.

* Examples added to the list in 2023.

Examples removed from the list in 2023

- Sword sheath ferrule. Korosten, Oblast Žitomir, Ukraine. Gosudarstvennyj Istoričeskij Muzej, Moscow 105009,inv. 2575/1.

Litterature

Graham-Campbell, James, 2013. Viking Art.

Fuglesang, Signe Horn, 1982. ‘Early Viking Art.’ Acta ad Archaeologiam et Artium Historiam Pertinentia (Series altera in 8°) 125–173.