Early Animal Style

December 19, 2022

The Anatomy of Germanic Art

- Introduction

- Early Animal Style

- Style I

- Style II/B

- Style II/C

- Style II/D

The Anatomy of Early Animal Style

c. 375 – 475

Shapes

1. Geometric ornamentation: triquetras/triskelions, arches, circles, triangles and dots.

2. Heads in Profile

3. Round Eyes

4. Open outwards-curling jaws

5. Pointy chin.

6. Boat-shaped ears.

7. Simple, almost almond-shaped hips.

8. Feet with toe-fronds.

Outlines

Even outlines without tapering or indents.

Flow

Simple wavy curves.

A. S-shapes.

Pattern

- Interlace rarely occurs.

- Loose interlace with visible background.

- Single-stranded ribbons.

- Double-stranded ribbons.

- Triple-stranded ribbons.

- Uniform line widths.

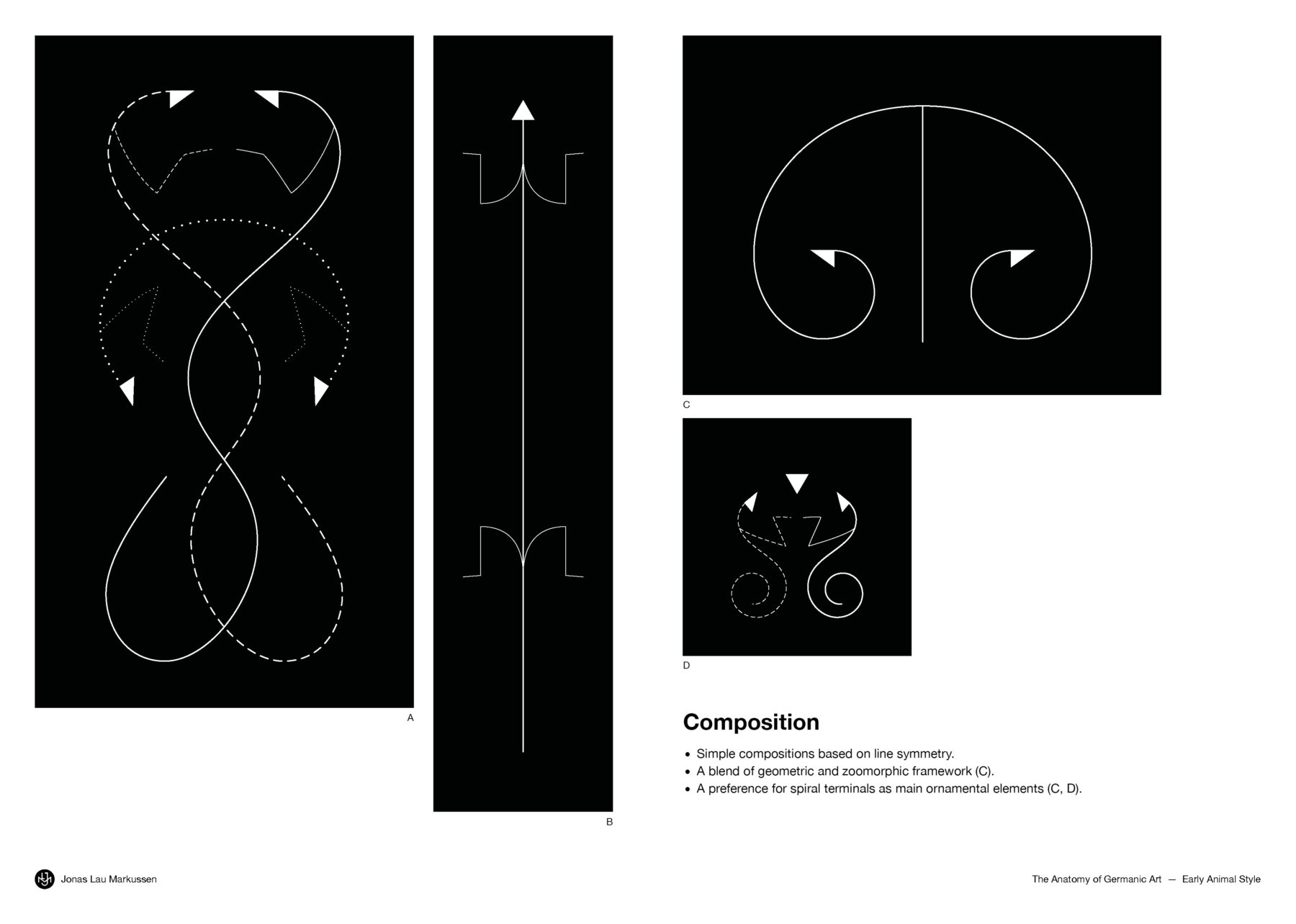

Composition

- Simple compositions based on line symmetry.

- A blend of geometric and zoomorphic framework (C).

- A preference for spiral terminals as main ornamental elements (C, D).

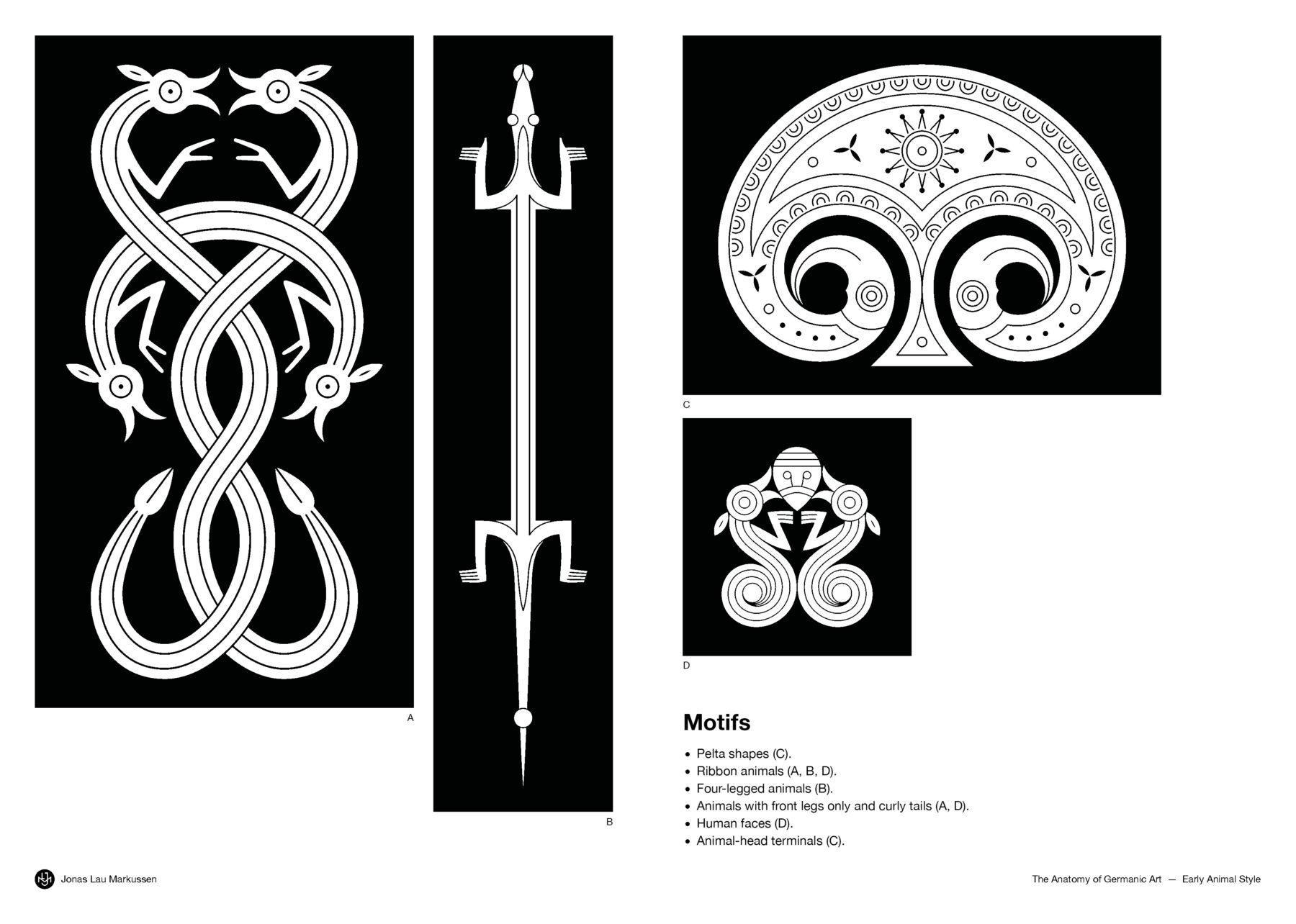

Motifs

- Pelta shapes (C).

- Ribbon animals (A, B, D).

- Four-legged animals (B).

- Animals with front legs only and curly tails (A, D).

- Human faces (D).

- Animal-head terminals (C).

The Migration Period Begins

The Migration Period

The Migration Period, from approximately 375 to 568 CE, was a dynamic era marked by significant movements of peoples across Europe. Various tribes and cultures interacted, clashed, and reconfigured the continent during this time, reshaping political boundaries, cultural landscapes, and power dynamics.

The Advance of the Huns

At the heart of the Migration Period were the Huns, a nomadic warrior people originating from Central Asia. Led by Attila, the Huns swept across Europe, leaving a lasting impact on the region. Their military prowess and swift cavalry attacks disrupted the Roman Empire and forced other tribes to migrate. The Völsunga saga, a Nordic epic, recounts the defeat of the Burgundians by Roman-Hunnic forces in the Battle of Worms, modern-day Germany, in 436. This clash exemplified the collision of cultures and the shifting alliances that characterised the Migration Period.

Division of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire faced internal strife and external pressures, not least from the Huns. In 324, Emperor Constantine I shifted the capital from Nicomedia to Byzantium, renaming it Constantinople and inaugurating a new era. Constantine’s spiritual awakening and victories in battle, supported by the deity Apollo, solidified his rule. However, Christianity became the Roman Empire’s state religion under Theodosius I in 394 and by 395, the Roman Empire was administratively split into two halves, with separate capitals and emperors: the Western Roman Empire, with its capital in Ravenna and the Eastern Roman Empire, centred in Constantinople.

Visigoths and Ostrogoths

Among the migrating tribes were the Goths, originally from the north, who played a pivotal role. When the Huns attacked, half of the Goths migrated westward, becoming the Visigoths, while the remaining Goths submitted to the Huns, becoming the Ostrogoths. Alaric I became the inaugural king of the Visigoths. His reign is notable for the sacking of Rome in 410, a pivotal event in the decline of the Western Roman Empire. Later, in 418, Emperor Honorius rewarded Visigothic federates by granting them land in Gallia Aquitania after these federates had attacked the Suebi, Vandals, and Alans.

Roman Withdrawal from Britain

In Britain, the withdrawal of Roman legions following Rome’s decline left a power vacuum, allowing Germanic tribes from the continent to establish footholds on the islands. British kings sought alliances with Saxon leaders, leading to the gradual influx of Germanic tribes.

Scandinavian Power Centres

Helgö, the predecessor to Björkö, emerged as a vital trading centre in Lake Mälaren, Sweden, around 200. Its strategic location facilitated commerce and cultural exchange. Early settlers established a thriving community engaged in trade and craftsmanship. However, Gudme, situated on Fyn, was Scandinavia’s most significant centre of wealth during the Iron Age. The first Gudme hall was built c. 300 and came to play a pivotal role until the second half of the 5th century. The settlement included a magnate’s farm and nearly 50 smaller farms. Another prominent site was Sorte Muld, a prosperous Iron Age settlement located 2 km southwest of Svaneke on Bornholm. During the Germanic Iron Age, it became one of Scandinavia’s most important centres. The earliest phase of Danevirke, a massive defensive earthwork, was constructed during this period. Stretching across the Jylland peninsula, it served as a bulwark against potential invasions from the south. The Danevirke reflected the strategic importance of controlling access points along trade routes and waterways in and out of the Scandinavian regions.

Taking Shape

Development

In the period leading up to the Germanic Iron Age, the art and ornamentation were dominated by simple geometric shapes, either as compositional motifs or punch ornamentation, mixed with simple figurative motifs of human figures and animals. Figurative motifs often appear in sequences like contemporary comics to tell stories and convey specific meanings that, unfortunately, are now lost to us. Other motifs seem more ornamental in nature. So-called pelta shapes, resembling a crescent moon or similar simple geometric figures with animal head terminals, are common. Serpent-like ribbon animals occur, but they look like distant relatives to the animals of the later well-known intricate knotwork patterns. They are usually limited to singular S-shaped animals adorning the edges of brooches and other artefacts. Brooches and other items were greatly influenced by models from continental Europe. This also applies to geometric decoration and the use of animals and human figures in ornamentation, although they were adapted to fit Scandinavian sensibilities. Traditionally, this period is commonly divided into two sub-periods Sösdala Style followed by Nydam Style, based on findings from each place. However, they seem to be stylistically very similar, if not indistinguishable.

Sösdala Horse Tack

The horse tack from Sösdala has given name to the first half of the period. The material characteristically features pelta shapes with animal-head terminals and punch decorations.

Nydam Swords and Sheaths

Pelta shapes and punch ornamentation prominently appear in the Nydam material, too. The anatomy of animals and animal heads are similar to those of Sösdala. However, we also see ribbon animals on some wooden Nydam sword sheaths.

Bow Brooches

Some of the earliest exquisitely decorated bow brooches appear in this period. Continental European models directly inspired them, but the model were quickly adapted to suit Scandinavian aesthetics. Carpet-pattern compositions of animals and geometric patterns are common.

The Golden Horns

On the two horns from Gallehus, we find some of the early figurative imagery that probably developed into or inspired the animal ornamentation in the subsequent Germanic Iron Age styles. We see apparent images of a Scandinavian story world. Although the stories and meaning are lost to us now, they feature motifs iterated in later artwork, like the bracteates, helmet plates and gold foil figures. Horned male figures with spears surrounded by animals, female figures with long hair carrying horns and humanoid figures with animal heads carrying weapons are some of the motifs showing up again in imagery on later artefacts throughout the Germanic Iron Age and into the Viking Age.

Examples

Examples on Gelmir.com →

A list of examples with photos, info and links to sources.

Belt Mounts

Nydam, Jylland, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, -.

Brooch — Hol

Hol, Trøndelag, Norway.

NTNU Vitenskapsmuseet, Trondheim, T9826.

Brooch — Skerne

Skerne, Falster, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, C288.

Equal-armed Brooch — Galsted

Galsted, Jylland, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, DCCXXXVIII.

Equal-armed Brooch — Hol

Hol, Trøndelag, Norway.

NTNU Vitenskapsmuseet, Trondheim, T9823.000.

Horn (short)

Gallehus, Jylland, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, 19015.

Horn (long)

Gallehus, Jylland, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, 18964.

Horse Tack — Sösdala

Sösdala, Skåne, Sweden.

Historiska Museet i Lund, Lund, 25 570.

Horse Tack — Fulltofta

Fulltofta, Skåne, Sweden.

Historiska Museet i Lund, Lund, 14 080.

Sheath — Kragehul

Kragehul, Fyn, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, C2250-22469.

Sheath — Nydam, NM. NV. 7311

Nydam, Als, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, NM. NV. 7311.

Sheath — Nydam, –

Nydam, Als, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, -.

Sheath Mounts

Ejsbøl Mose, Jylland, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, HAM E10976; HAM E8940; HAM E9068; HAM E7724; HAM E9287; HAM E9286.

Square-headed Brooch — Hol

Hol, Trøndelag, Norway.

NTNU Vitenskapsmuseet, Trondheim, T9822.000.

Square-headed Brooch — Lunde

Lunde, Agder, Norway.

Universitetsmuseet i Bergen, Bergen, B3543.

Sword — Kragehul

Kragehul, Fyn, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, MDLXXXI.