Gold Foil Figures

June 15, 2022

The Anatomy of Germanic Art

- Introduction

- Early Animal Style

- Style I

- Style II/B

- Gold Foil Figures

- Helmet Plates

- Style II/C

- Style II/D

The Anatomy of Gold Foil Figures

c. 525 – 675

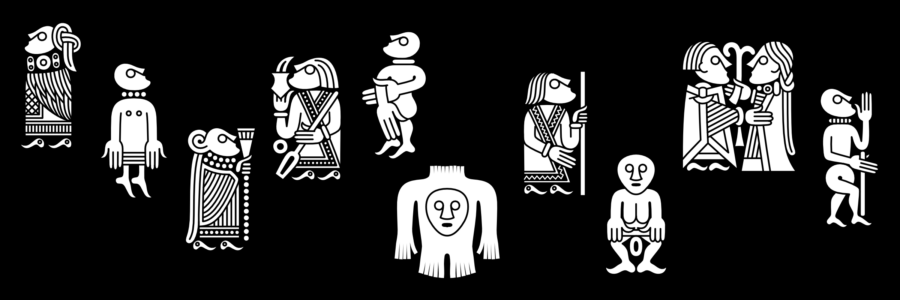

Motifs

- Single figures in female attire and haircut (A, B)

- Single figures in male attire and haircut (C, D)

- Pairs (E)

- Figures with the Seer’s thumb gesture (F).

- Figures with the crossed legs posture (F).

- Figures with the grasping wrist gesture (G).

- Figures with the open palms gesture (G).

- Naked figures with primary sexual markers (I).

- Figures with their bodies cut out of the foil (J).

Gold Foil Figures

Gold foil figures are tiny sheets of gold with stamped depictions of mostly human figures, either singular or in pairs. They are typically found in and around post-holes of notable buildings in central settlements. Others have been found in bogs or natural wells, and a few as part of burials and hoards.

Manufacture

Unlike most gold bracteates, gold foil figures are often made of low-grade gold alloys, which makes the foil brittle and less malleable. The foils are usually less than 50 mm in size and under 1 mm thick. The motifs were stamped into the gold sheet from the backside using a positive bronze die (patrix), and the excess material was cut with a knife after stamping. More than 725 unique die impressions exist, including 22 dies, with the most popular examples producing over a hundred stamped foils each. Most dies, though, are only represented by a few stamped foils. 89 cut figures also exist. Further modification of the figures after their initial production is not unusual. Details could be scratched or punched in. Tiny strands of gold might be added to feature as jewellery or genitalia, and the foil could be bent, for example, to mimic a seated position or crumbled up or even torn into pieces.

Function

The exact function of the gold foil figures is disputed. The most typical find context is in and around postholes of notable buildings, especially temples like the one in Uppåkra, Sweden. Others have been found at a natural well in Bornholm, Denmark. These contexts, often directly connected to places of veneration, point to votive offerings as the primary function, either deposited in conjunction with the erection of central profane and sacred buildings or at devotional sites in nature. Gold was regarded as a material with magical capabilities connected to divine powers, and in mythology, dwarven smiths were known for creating material things and animated beings. The alteration of the figures after their initial creation by the smith may indicate that the gold foil figures might have been perceived as magical beings with performative capacity rather than mere symbolic representations of deities or people.

Inspiration

The images of the foils are, in many ways, a direct development of the style of the gold bracteates, possibly incorporating further classical motifs while maintaining a distinctly Scandinavian style and imagery.

Dating

Gold foil figures are difficult to date. Excavations at Sorte Muld and Uppåkra suggest c. 525 to 700. Some have been associated with Viking Age contexts, but this should be viewed with caution as they could have easily been deposited earlier. Stylistically, the gold foil figures are within the category of Style II/B, which also points to them emerging in the first half of the 6th century and declining in production at the end of the 7th century.

Distribution

Gold foil figures are found throughout Scandinavia, and the vast majority of the 3243 figures are found in settlement areas in Southern Scandinavia, notably 2480 at Sorte Muld, Bornholm and 127 at the temple at Uppåkra. 22 bronze dies have been found, most of them at Bornholm, Skåne and Sjælland.

Gender and Presentation

Although specific visual cues like hairstyles, attire and attributes are distinctly gender-coded, it is not possible in most cases to categorise individual figures as being unambiguously of either sex. Among the known 644 single figures and 179 pairs, roughly less than half can be confidently categorised as either male or female-presenting, with a rather heavy lean towards male figures. Since the bulk of the figures may not be attributed to the male or female gender, this way of categorising does largely not seem to have been essential. Gender ambiguity in any instance, as with the figures on the gold bracteates, could easily be a substantial quality rather than an error. Especially when it comes to the context of supernatural relation-making and shamanistic practices, gender transgression was, although considered taboo culturally, undeniably imbued with magical capacity and power.

Primary sexual markers

Primary sexual markers, like penis, vagina, breasts and beard, are rare.

Costume

Although the kaftan featured on several foils is first known in Scandinavia from archaeological contexts from the Viking Age, the costumes depicted largely reflect real-world characteristics of the time, so much so that the figures played an essential role in reconstructing the Scandinavian women’s dress from the Germanic Iron Age. Longer and layered garments often indicate female figures, while shorter tunics and kaftans indicate male figures. Female attire typically consists of various types of outer garments, such as cloaks or capes that rest on the shoulders and are open in the front. Jackets also occur. The inner garments consist of long dresses. Hair is worn long and tied in a knot with a lengthy pigtail. Jewellery also occur. The male attire typically comprises a long or short kaftan with an overlapping front. Outer garments like capes occur occasionally but differ from women’s by being closed at the shoulder. The hair is worn shoulder-length. Both genders wear plain tunic-like shirts or dresses. The man-woman pairs are sometimes even stylistically assimilated, presumably underlining the unity of the two persons, occasionally to a degree of gender-neutral mirror images. Although trousers and sleeves are well-known garments from this period, they are rarely articulated, and it is usually impossible to distinguish between cuffs and arm rings.

Attributes

Female attributes are drinking horns and disc-on-bow brooches across the neck, often only represented by a few simple dots or a line. Male attributes are staves, neck rings (predominantly on naked figures), arm rings on the upper right arm and drinking beakers. Staffs and neck rings were associated with magical and aristocratic power in the early Antique around the Mediterranean. The neck ring is continually associated with deity and aristocracy and plays an essential role in the Germanic Iron Age sagas and myths (e.g., Odin’s ring, Draupnir).

Gestures and Possible Interpretations

Many hand and arm positions may be incidental or represent a neutral position, while other gestures probably convey some kind of meaning. Some seem to imitate Antique and Late Antique gestures often shared with the bracteates, others have possible Christian affinities, and some are otherwise known only from later medieval descriptions or illustrations.

The Seer’s Thumb

The thumb of the figure’s hand is placed close to or in the mouth, often seen in conjunction with crossed legs. The gesture appears already in Style I imagery and survived into the Viking Age and in Christian iconography as an expression of foresight or prophesy combined with an element of magic.

Crossed Legs

One of the figure’s legs is bent and crossed over the other straight leg. The cross-legged posture is possibly apotropaic (averting evil) in origin.

Open Palms

The figure is depicted with arms down the sides and palms facing forward. This gesture is often seen in late antiquity Christian context (as with raised arms), where it is apotropaic or signals reverence, fear or submission.

Grasping Wrist

The figure grasps around their wrist, thereby locking the hand. The gesture demonstrates reverence in the presence of higher powers.

Abundantia

The Classical Abundantia motif is a predominantly ‘horn-shaped’ object appearing from the top of a beaker, implying that the person is drinking or carrying out a beaker filled to the brim.

A Sacred Wedding

It has been proposed that the pairs represent a sacred wedding, ‘hieros gamos’, similar to that of Gerd and Freyr, with references to fertility and regeneration. However, it is generally impossible to convincingly link any figures directly to characters of the Nordic Mythology’s pantheon based on their appearance or attributes. Clues for interpreting some figures might, however, be found in later medieval folklore from Southern Scandinavia, especially regarding the figures from Guldhullet, Bornholm.

Elven Women

In medieval folklore, elven women are connected to lakes, streams and bogs. They are beautiful but dangerous creatures. They can enchant people, and sexual intercourse with one leads to losing one’s soul. The elven woman Slattenlangpat (directly translates to ‘saggy-long-tits’) is described with her breasts hanging below her waist. Her long breasts symbolise fertility, and with them, she feeds her fish children by laying down on a rock or bridge by the river and tossing her tits out into the water. Every night, she is chased and caught by the Nightrider, a figure with solid connotations to Odin. Followed by dogs, he flies away with her splayed across his horse. The next night, she comes back to life, and the hunt starts over. Thus, a tiny elven woman in gold might have been a suitable sacrifice to Odin, as this was what he put down on his nocturnal hunts.

Trolls

The headless troll with a face in its stomach is known from later medieval depictions (Blemmyes). Folktales about Thor in conflict with trolls are especially known in Småland. According to legend, trolls sought protection in the houses of people. A votive offering of a tiny golden troll to Thor may be interpreted as a preemptive measure. The household had thus given Thor a troll, so he didn’t have to blow lightning down into the farm to kill the troll possibly hiding there.

Examples

Examples on Gelmir.com →

A list of examples with photos, info and links to sources.

Gold Foil Figure — Gudme

Gudme, Fyn, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, DNF 57/83.

Gold Foil Figures — Guldhullet

Guldhullet, Bornholm, Denmark.

Gold Foil Figures — Hauge

Hauge, Rogaland, Norway.

Universitetsmuseet i Bergen, Bergen, B5392.

Gold Foil Figures — Helgö

Helgö, Uppland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 108639; 109960; 110369; 110370; 110371; 110372; 110373; 110374; 110376; 110377; 110378; 110379; 110380; 110381; 110382; 110383; 110384; 110385; 110386; 110387; 110389; 110394; 110395; 110417; 110418; 110419; 126241.

Gold Foil Figures — Håringe

Håringe, Småland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 109957; 109958.

Gold Foil Figures — Lundeborg

Lundeborg, Fyn, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, 6407/86.

Gold Foil Figures — Mære

Mære, Trøndelag, Norway.

NTNU Vitenskapsmuseet, Trondheim, T18842.

Gold foil figures — St. Smørengegård NV

St. Smørengegård NV, Bornholm, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, C38757; C39622.

Gold Foil Figures — Sorte Muld

Sorte Muld, Bornholm, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, 6255/85.

Gold Foil Figure Patrice

Eketorps Sättuna, Östergötland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 3044333.

Litterature

Gold Foil Figures in focus, 2019.

Skalk 2018:4

Skalk 2018:5

Sorte Muld, 2008.

Back Danielsson, Ing-Marie, 2010. Go Figure! Creating Intertwined Worlds in the Scandinavian Late Iron Age (AD 550–1050)

Back Danielsson, Ing-Marie, 2016. Materials of Affect. Miniatures in the Scandinavian Late Iron Age (AD 550–1050)