Further Figurative Motifs

September 26, 2022

The Anatomy of Germanic Art

- Introduction

- Early Animal Style

- Style I

- Style II/B

- Style II/C

- Style II/D

- Further Figurative Motifs

The Anatomy of Further Figurative Motifs

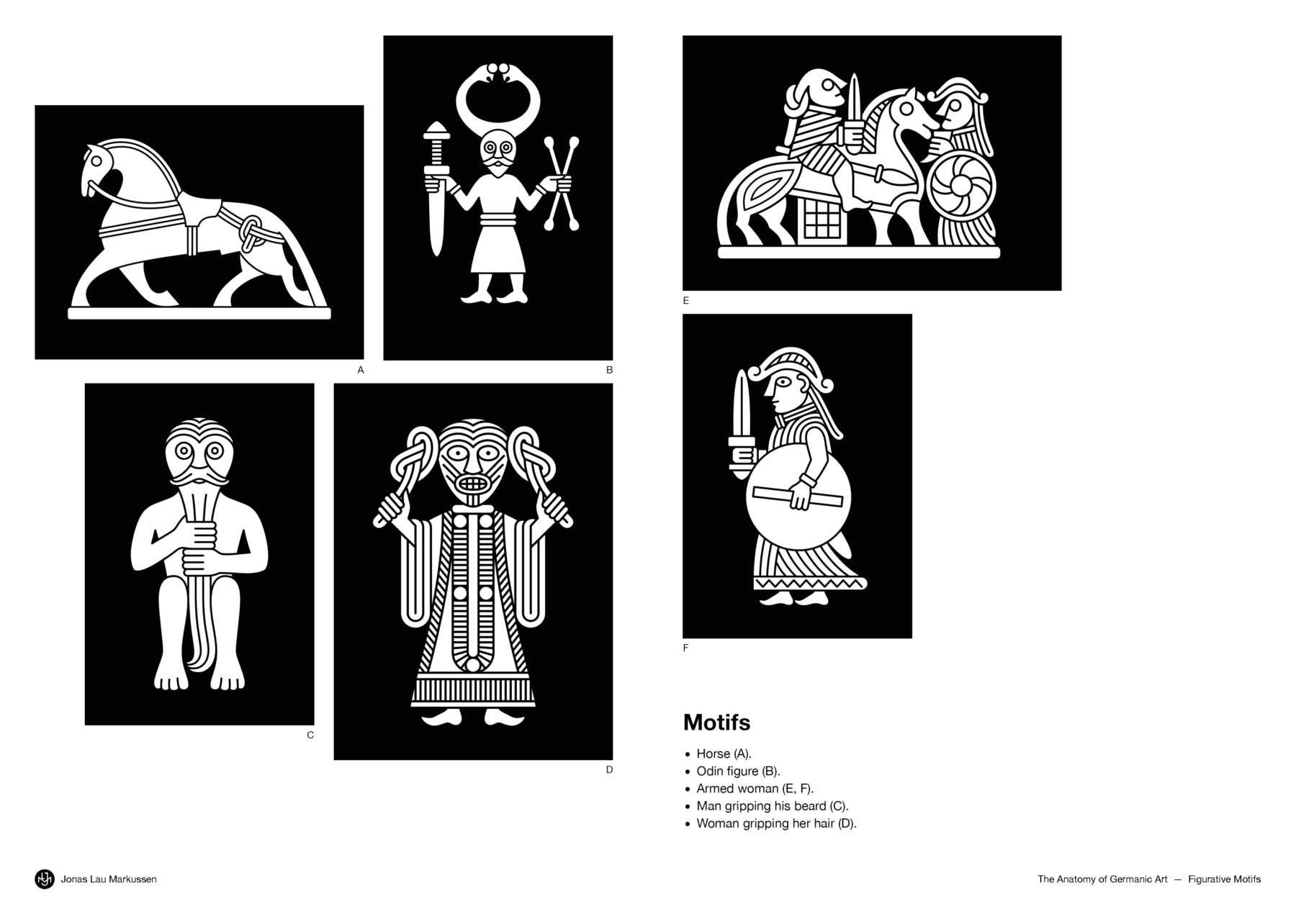

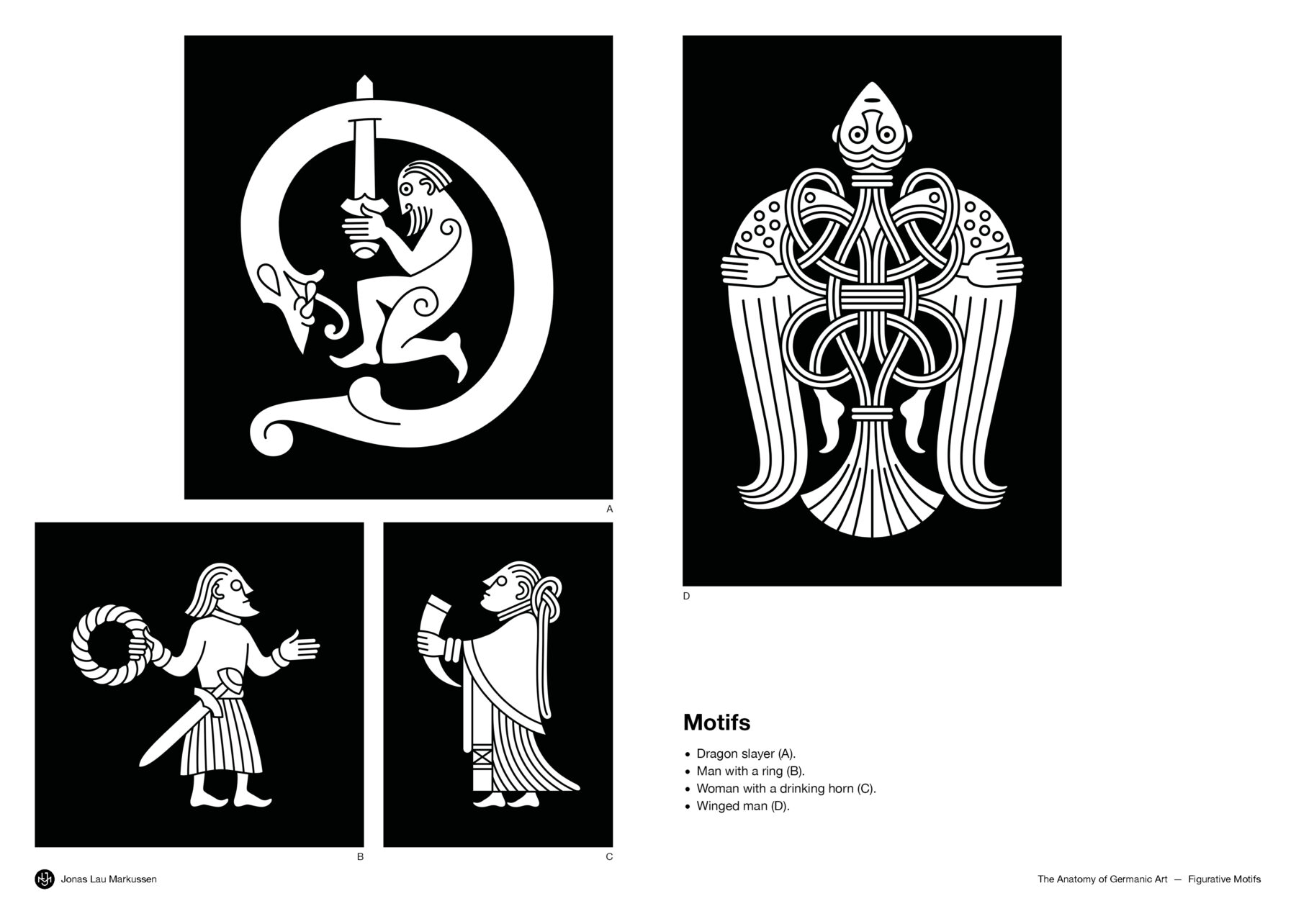

Motifs

- Horse (A).

- Odin figure (B).

- Armed woman (E, F).

- Man gripping his beard (C).

- Woman gripping her hair (D).

- Dragon slayer (A).

- Man with a ring (B).

- Woman with a drinking horn (C).

- Winged man (D).

Further Figurative Motifs

Figurative motifs played an essential role in the decorative art of the Germanic Iron Age in tight connection to animal ornament, especially in the first half, exemplified by the imagery of the gold bracteates and helmet plates. However, moving into the Viking Age, animal ornament with its ribbon animals and gripping beasts took centre stage in the ornamentation, pushing the figurative motifs into a secondary role. While figurative art is featured side by side with the animal ornament, as seen on the prestige helmets, in Germanic Iron Age art, it is often absent or plays a supporting role in the Viking Age. A confident emphasis on the transformative shapeshifting characteristic of animal ornament was the overwhelmingly popular choice in late Germanic Iron Age and Early Viking Age art. When figurative motifs occur, they usually underscore or play directly into this focus on magical transfiguration and the invocation of transformative liminal power. It is only in the post-conversion late Viking Age art that figurative motifs regain prevalence in the role of being juxtaposed with animal ornament. However, now, in a more representative symbolic manner than earlier, as seen on several runestones, not least on the Greater Jelling Stone with its depiction of the crucifixion of Christ.

Horses

Horses are not surprisingly a common motif in Germanic Iron Age and Viking Age art. They are often mounted but also occur riderless, usually pacing, with or without tack. A horse featuring tack and saddle is significant, as it marks it specifically as a trained steed and presumably a warrior’s horse, as seen on the battle scenes on the helmet plates. Male horses were preferred for burial sacrifice in the Viking Age, and the male gender of a horse figure is often explicitly indicated by its genitals. Though horse depictions were common throughout Europe, including Scandinavia, the riderless single-horse motif may have Carolingian influences.

Odin Figures

The popular Odin figures of the Germanic Iron Age still occur going into the Viking Age. However, the visual representation of the Odin complex seems to shift towards a preference for depicting armed women, valkyries, in the early 9th century, instead of the half-naked spear-bearing men with horned headdresses accompanied by beast-headed men.

Two Armed Women

In the 9th century, valkyries seemed to have been the preferred motif representing the Odin complex. They usually have their hair in a knot and a long ponytail in accordance with women’s fashion, and they wear a long dress and apron. Disc-on-bow brooches occur, too. In addition to their female attire, they carry shields, swords, and helmets, which conventionally belong to the masculine sphere of warfare in early medieval Scandinavia. Valkyrie depictions span a spectrum of typical variations, with three motifs composing the main groups: an armed mounted woman, an armed woman on foot with a shield and sword, and a woman in normative women’s attire carrying a drinking horn. A common configuration is that of an armed mounted woman being received by an armed woman on foot with a shield, who presents the rider with a drinking horn. This motif is directly related to the Gotland picture stones, where a bearded man on an often eight-legged horse is welcomed by a woman in female attire who holds forth a drinking horn. The motif on the picture stones is most likely a scene from the Völsunga saga involving Sigurd, the dragon slayer, on his horse Grani, a descendant of Odin’s eight-legged horse Sleipnir, and the valkyrie Brynhild (also known as Sigrdrífa).

The Saddle Cloth

Below the stomach of the mounted valkyrie’s horse hangs a square cloth divided into nine equal sections. In the stories Jómsvíkinga saga and Darraðarljóð, a group of valkyries weaves a piece of cloth on a loom before heading to the battlefield to collect the slain warriors. The loom’s frame is made of spears, and the shed stick is a sword. The warp and weft are made of the intestines of men, and the weights are skulls. When they are done weaving, they tear the cloth apart, each taking a piece of it with them. The craft of weaving belongs to the realm of women in early medieval Scandinavia and is directly connected to seiðr, the practice of magic and divination. The word seiðr originally meant string, ribbon or thread. This connects them directly to the ambiguous and fluid group of norns and disir, all deities belonging to the realm of womanhood.

Armed Woman

Until the images of valkyries appeared in the 9th century, there were no previous examples of depictions of armed women in early medieval Scandinavia. The societal expectation of the time was to act in accordance with one’s assigned gender. Crossing the boundaries of the binary gender roles was usually harshly condemned and could have severe negative implications for the individual, as well as their family. However, the act of gender transgression was also an act of stepping into a liminal and supernatural space. At the same time, exceedingly dangerous and uncontrollable, as well as extraordinarily magical and thus exceptionally powerful. The valkyries, by taking up arms and thereby acting in a distinctly masculine manner while at the same time engaging in normative female activities like weaving and wearing dresses, clearly operate in this liminal and extra-potent, hyper-pregnant supernatural space.

Woman with a Drinking Horn

Depictions of female figures carrying drinking horns and cups date back to the gold foil figures of the 6th century and even earlier. They most notably appear on the Gotland stones and valkyrie pendants of the 9th century and, later, again on the Sigurd stones of the late Viking Age. Although they are usually dressed exclusively in women’s wear, they seem to be directly connected to the mythological valkyries, notably in the Völsunga saga where Sigurd meets the valkyrie Brynhild, a scene depicted plenty across the span of the Viking age in which she is usually shown in a dress holding forth a drinking horn to greet Sigurd.

Gripping One’s Hair and Beard

The gesture of gripping one’s own hair or beard appears to have been introduced in the early Viking Age and seems to have magical connotations and links to shape-shifting. Ribbon animals gripping their own and other animals’ limbs were already prevalent since the migration period (Style I and onwards). But the hair and beard gripping gesture emerges with the gripping beasts of Broa style (c. 750-825) and further develops and increases its prevalence through the Oseberg and Borre style (c. 800-950).

Woman Gripping Her Hair

Several depictions are known of human figures viewed from the front grasping the pigtails of their centre-parted hair, one in each hand. The pigtails are typically tied in pretzel knots at the root. The figure’s mouth is usually accentuated in some way with lines around or across it, sometimes resembling gritting teeth, and some have a tongue-like shape protruding from it. Although the long hair, knots, and long robes the figures wear are usually feminine signifiers, the gender is still somewhat ambiguous. It is, for example, not always clear if the lines around the mouth are meant to depict some kind of beard. The motif is predominantly dated to the 9th century, but a related motif can be seen on the so-called ‘Snake-witch stone’ with a design in Style II/B from around 600 found at Smiss on Gotland. The figure on the stone wears the same hairdo with tied pigtails, but instead of gripping their hair, the figure is gripping two snakes positioned at each side of the head with their heads in profile facing the figure. In this way, the Smiss stone’s composition mirrors the motif of two beasts flanking a male warrior seen on several helmet plates. The visual emphasis on these types of figures’ mouths and the connection to the motifs on the helmet plates hint at a figure engaging in magic and linking it to the practice of shapeshifting.

Man Gripping His Beard

A seated male figure grasping his long beard is a recurring motif in the Viking Age. Figures gripping their beard originate in the gripping beasts of the Broa style and are especially common in the Oseberg style. The gesture continues into the late Viking Age in the shape of what seems to be board game pieces of seated men grasping their phallic beards, sometimes also featuring an erect penis.

Winged Man

Winged men are a common motif in the Viking Age, not least on several scabbard mounts from the 10th to 11th century, and bird brooches with male faces on their backs are even known from a couple of centuries before the Viking Age. Both are expressions of the practice of shapeshifting, and magic feather cloaks are well-known in the mythology and the sagas, where several of the Æsir and Jotnar transform into birds to travel through the skies and transcend the boundaries of the material world. Especially the stories about Völund the smith known from Völundarkvida and Thidrekssaga are noteworthy when it comes to man-bird depictions, as he is clearly the one taking the shape of a mount from Uppåkra, Sweden, probably from the 9th century, and scenes from the story about him are also pictured on the Gotland picture stones. In the story, Völund is linked to the valkyries, as he is married to one capable of taking a swan’s shape. His status as a smith who creates riches and magical items like his feather cloak even ties him to the mythological dwarves. Common to most of these depictions comprised of simple but effective interlace knots composing a man in a feather-cloak contraption is that it is unclear where the man’s body stops and where the bird’s body begins. They are literally merged. On the Gotland picture stones, Völund’s story is juxtaposed with scenes from the Völsunga saga featuring Sigurd (who was raised by the dwarf Reginn) and the Valkyrie Brynhild. The common theme is most likely revenge; Völund takes revenge on king Nidud, who captured and disabled him, and Brynhild on Sigurd, who betrayed her.

Dragon Slayer

The Völsunga saga, featuring Sigurd, the dragon slayer, was incredibly popular in the Viking Age. Scenes from the story are depicted on several Gotland picture stones and multiple runestones. The event of Sigurd slaying the dragon is prevalent among the Völsunga saga runestone depictions. Although the saga events take place centuries before the Viking Age, when Scandinavia was heathen, they are still exceptionally popular and prominently featured on Christian stones raised after the conversion. The fact that the Völsunga saga revolves around heathen deities and mythological themes and figures was apparently unproblematic in post-conversion Scandinavia. However, this might have been possible because the central figures of the saga break with old traditions in the narrative. It was, perhaps, even possible to see Sigurd acting as a symbol of Saint Michael’s dragon killing.

Man with a Ring

The motif of a man in profile holding a ring in one hand is known from little pendant figurines and several rune stones. On the stones, he is placed opposite a woman with a drinking horn facing him. Above them is the scene of Sigurd piercing the dragon, Fafnir, with his sword, Gram. A plausible interpretation is that the two figures facing each other depict the meeting of Sigurd and the valkyrie Brynhild after he had killed Fafnir. The cursed ring Andvaranaut in his hand represents the treasure he won by slaying the dragon, as well as his impending betrayal of Brynhild. A betrayal that will ultimately lead to their death through Brynhild’s revenge.

Examples

Examples on Gelmir.com →

A list of examples with photos, info and links to sources.

Bird-and-man-shaped brooch

Øster Nordlunde, Lolland, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, C43758.

Bowl

Lejre, Sjælland, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, 11373.

Ear spoon

Björkö, Uppland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 456867.

Horse-shaped brooch

Vestergård, Sjælland, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, C42767.

Man-shaped figurine – Eyrarland

Eyrarland, Eyjafjarðarsýsla, Iceland.

Þjóðminjasafn Íslands, Reykjavík, 10880/1930-287.

Man-shaped figurine — Fedet

Fedet, Sjælland, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, C24292.

Man-shaped figurine — Rällinge

Rällinge, Södermanland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 109037.

Man-shaped pendant

Klahammar, Södermanland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 1370416.

Odin figure — Ekhammar

Ekhammar, Uppland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 8045.

Picture stone — Ardre

Ardre, Gotland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 108199.

Picture stone — Lillbjärs

Lillbjärs, Gotland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 45680.

Picture stone — Stora Hammars

Stora Hammars, Gotland, Sweden.

Bungemuseet, Fårösund, 108206.

Picture stone — Smiss, 108202

Smiss, Gotland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 108202.

Picture stone — Smiss, GFC10261

Smiss, Gotland, Sweden.

Gotlands Museum, Visby, GFC10261, Smiss 3.

Picture stone — Tjängvide

Tjängvide, Gotland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 108203.

Picture stone — Tängelgårda, 44501

Tängelgårda, Gotland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 44501.

Picture stone — Tängelgårda, 108186

Tängelgårda, Gotland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 108186.

Picture stone — Lillbjärs

Lillbjärs, Gotland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 45680.

Runestone – Ramsundsberget

Ramsundsberget, Mora, Södermanland, Sweden.

Runestone Drävle

Drävle (now Göksbo), Uppland, Sweden.

Sword scabbard chape

Bjergene, Sjælland, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, C34512.

Valkyrie brooch — Galgebakken

Galgebakken, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, C37110.

Valkyrie brooch — Kalmergården, KN855

Kalmergården, Sjælland, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, KN855.

Valkyrie brooch — Kalmergården, KN1591

Kalmergården, Sjælland, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, KN1591.

Valkyrie brooch — Sønder Tranders

Sønder Tranders, Jylland, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, C42888.

Valkyrie figurine

Hårby, Fyn, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, C39227.

Winged-man-shaped mount

Uppåkra, Skåne, Sweden.

Historiska museet vid Lunds universitet, Lund, -.

Woman-shaped jewelry

Fugledegård, Sjælland, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, FG3589.

Woman-shaped pendant

Aska, Östergötland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 107873.

Woman-shaped pendant — Björkö, 108915

Björkö, Uppland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 108915.

Woman-shaped pendant — Björkö

Björkö, Uppland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 108916.

Woman-shaped pendant — Köping

Köping, Öland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 108864.

Woman-shaped pendant — Nygård

Nygård, Bornholm, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, -.

Woman-shaped pendant — Tuna

Tuna, Uppland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 108947.

Literature

Helmbrecht, Michaela. 2013. Figures, foils and faces – fragments of a pictorial world. ACTA ARCHAEOLOGICA LUNDENSIA. SERIES IN 8°, No. 64

Helmbrecht, Michaela. 2012. A Winged Figure from Uppåkra. Fornvännen 107(3), 171–178.

Helmbrecht, Michaela. 2013. Smeden, der fløj. Skalk 2013, 3

Kastholm, Ole Tirup, 2014. En hårriver fra vikingetiden – nyt fra udgravningerne i Vindinge. ROMU, Årsskrift fra Roskilde Museum 2014. Roskilde.

Pentz, Peter. 2017. At spinde en ende. Skalk 2017, 1

Pentz, Peter. 2018. Viking art, Snorri Sturluson and some recent metal detector finds. Fornvännen 113.

Staecker, Jörn. 2006. Heroes, kings, and gods: DiscoveringsagasonGotlandicpicture-stones. Old Norse religion in long-term perspectives: Origins, changes, and interactions

Assembling the Full Cast: Ritual Performance, Gender Transgression and Iconographic Innovation in Viking-Age Ribe. Medieval Archaeology (2021).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00766097.2021.1923893