Urnes style

December 19, 2016

The Anatomy of Viking Art

- Introduction

- Broa Style

- Oseberg Style

- Borre Style

- Jelling Style

- Mammen Style

- Ringerike Style

- Urnes Style

The Anatomy of the Urnes Style

c. 1050 – 1125

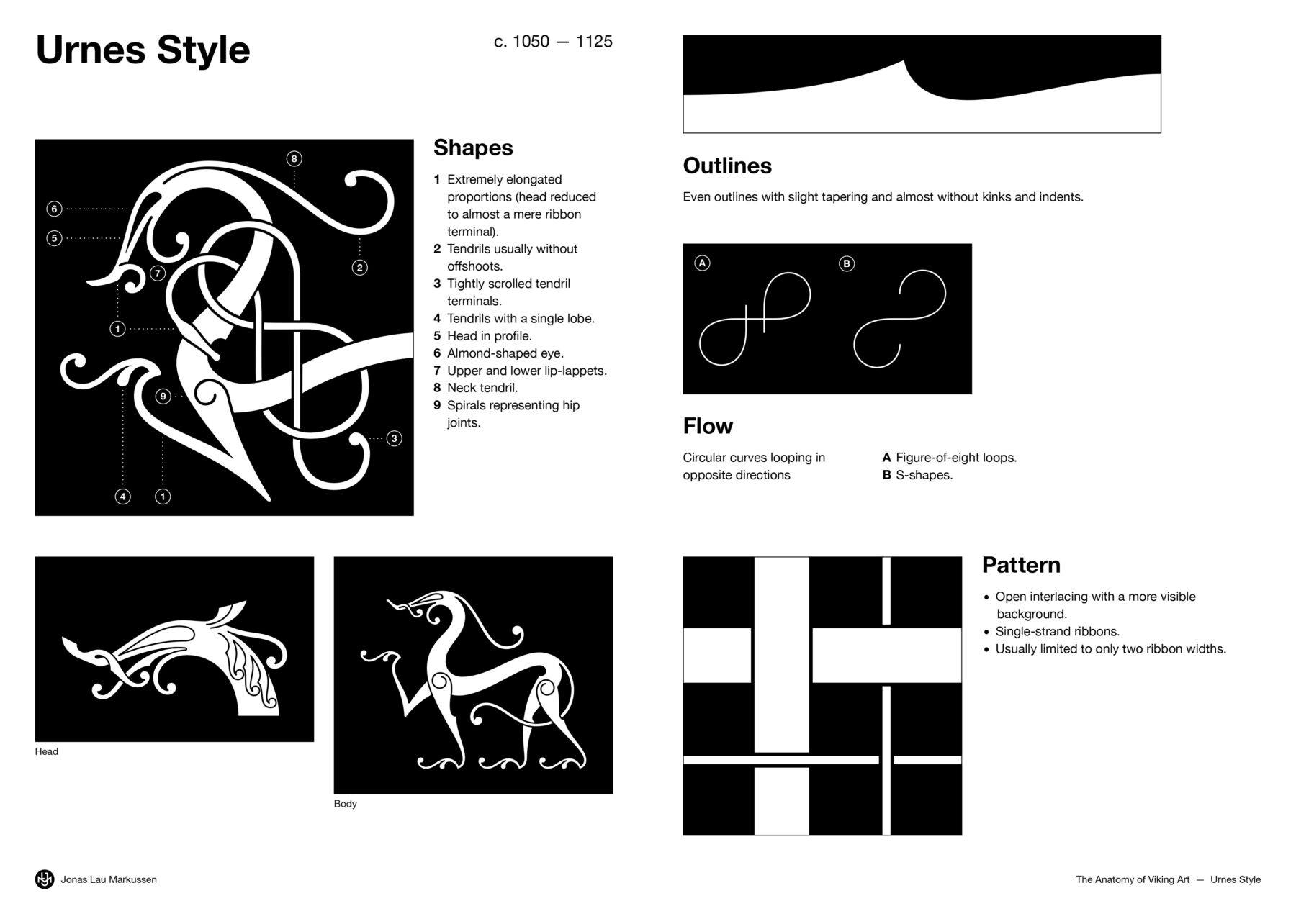

Shapes

1. Extremely elongated proportions (head reduced to almost a mere ribbon terminal).

2. Tendrils usually without offshoots.

3. Tightly scrolled tendril terminals.

4. Tendrils with a single lobe.

5. Head in profile.

6. Almond-shaped eye.

7. Upper and lower lip-lappets.

8. Neck tendril.

9. Spirals representing hip joints.

Outlines

Even outlines with slight tapering and almost without kinks and indents.

Flow

Circular curves looping in opposite directions.

A. Figure-of-eight loops.

B. S-shapes.

Pattern

- Open interlacing with a more visible background.

- Single-strand ribbons.

- Usually limited to only two ribbon widths.

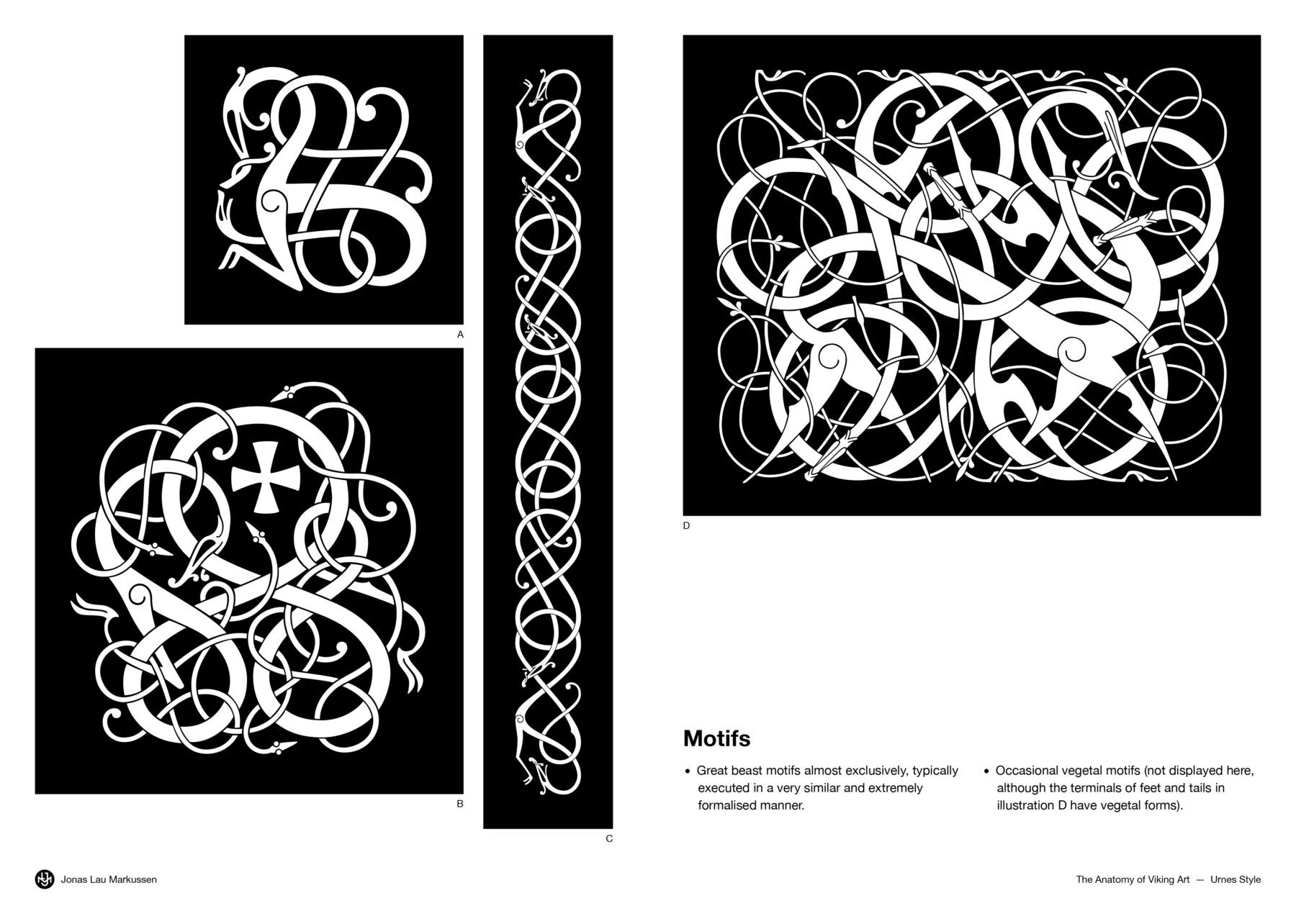

Composition

- Juxtaposed and interpenetrating ribbons of figure-of eight loops.

- Absence of axes and symmetry in composition.

- Balance in design is built by the fluid juxtaposition of the circular loops.

Motifs

- Great beast motifs almost exclusively, typically executed in a very similar and extremely formalised manner.

- Occasional vegetal motifs (not displayed here, although the terminals of feet and tails in illustration D have vegetal forms).

Consolidation of the Norse Regions

The Throne of Norway

Harald Hardrada, the half-brother of Olaf Haraldson, fled to Kievan Rus’ after he and Olaf were defeated at the Battle of Stiklestad. He became a captain in the army of Yaroslav the Wise, king of the Rus’, and later went to Constantinople, where he earned great honour and wealth serving in the Byzantine Varangian Guard. After fifteen years in the East, he returned to Norway just before the death of Magnus the Good, and soon became king of Norway.

The Throne of Denmark

Sweyn Estridsson, who had served under Magnus the Good, became king of Denmark. Though he was not a direct successor to Cnut, he was the closest living legitimate heir to the throne through his family connection to his mother, Cnut’s sister, Estrid Svendsdatter, and he took the matronymic surname Estridsson, emphasising his connection to the royal Danish bloodline. Sweyn is often considered Denmark’s last Viking Age king, as well as the first Medieval one.

The Norman Conquest of England

After securing his power as Duke of Normandy, William the Conqueror, who was a descendant of Rollo, launched the Norman Conquest of England and claimed the English throne. In his pursuit of the English crown, Harald Hardrada died in the Battle of Stamford Bridge, opposing the Anglo-Saxon king Harold Godwinson. Later that same year, Harold was defeated by William, who was then crowned king of England in London. A few years later Sweyn Estridsen made a couple of final attempts to reconquer the English throne to re-establish the Great Norse Kingdom, but failed. These events are traditionally considered to mark the end of the Viking Age.

The Conversion of Sweden

There were numerous attempts to convert the Swedish regions of Scandinavia, but they were not very successful, owing to the resistance of the Swedish people, with their deeply-rooted Norse beliefs and their strong traditions around the cult at Uppsala. None of the Christian Swedish kings had the strength or the support to force the conversion, until the reign of Inge the Elder, who was a devout Christian. He is known to have founded the first abbey in Sweden, and took harsh measures against ‘heathen’ practices.

European Integration

By now, all the Norse in Scandinavia and throughout Europe had converted to some form of Christianity. Their leaders grew dependent on the Church to support their rule, and at every level, the Scandinavian societies became increasingly similar in culture and customs to the rest of Continental Europe and the British Isles.

Old Norse Minimalism

Development

Where the Ringerike style skews towards a greater elaborateness, with patterns that feature numerous tendrils and offshoots, the Urnes style is much cleaner, and almost geometric and modern. Though the two styles may seem very different in their approach to the execution of animal ornament, they share many common characteristics, including an affinity for the great beast motif originated in the Mammen style. On the other hand, in the Urnes style, plant-based motifs have vastly diminished importance, although they are not entirely abandoned.

Dating

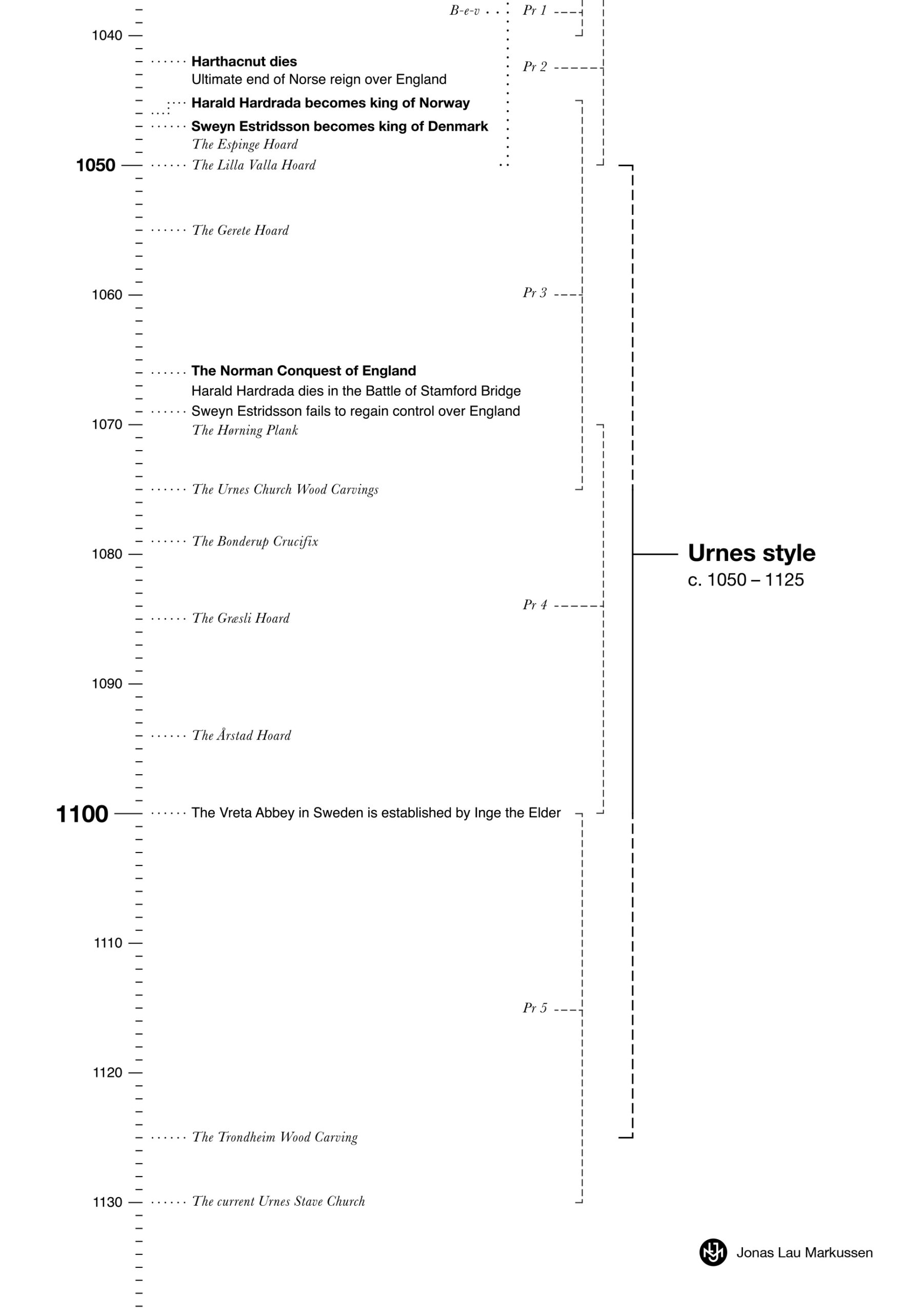

The Urnes style may be approximately dated through dendrochronological samples of the surviving wood carvings, and dateable coins found in hoards with Urnes-style metalwork.

The Runestone Styles

The development from the Ringerike style may be traced through a large number of runestones that span the transitional period, and are found mostly in Uppland, Sweden. The runestone styles are categorised as ‘Profile 1–5’ (Pr 1–5) and ‘Bird’s-eye-view’ (B-e-v). Pr 1, Pr 2 and the contemporary B-e-v pertain to the Ringerike style. Pr 3 is a transitional style that displays characteristics of both Ringerike and Urnes styles. Pr 4 is the Urnes style proper, and Pr 5 pertains to the late Urnes style.

The Jarlabanke Runestones

The runestones are virtually the only first-hand written sources authored by the Norse. They bear the names of those who raised the stones, as well as the names of those who the stones commemorate, and many of them were signed by the artists who created them, of which the runemasters Åsmund, Balle, Fot and Öpir are some of the best known. Through these runic texts, we get a tiny glimpse of the world view of the Norse. They describe events such as significant battles and the taking of Danegeld, also mentioned in sources outside of Scandinavia, and later medieval texts, such as the Icelandic sagas. From the inscriptions on a group of stones known as the Jarlabanke Runestones, we can piece together a reasonably cohesive picture of the family relations of the rich and influential Jarlabanke clan. The life of Estrid Sigfastdotter has been especially well-reconstructed based on the texts on runestones and other circumstantial evidence. She was the maternal grandmother of the chieftain Jarlabanke, a powerful woman born into the Swedish royal milieu, and one of the earliest known Christians in Sweden.

Openwork Brooches

A common Urnes-style find is the small openwork brooch featuring the great beast motif. The exact execution varies, but they all display a relatively simple figure-of-eight loop interlacing of a large animal fighting one or two smaller and thinner serpents.

The Urnes Stave Church

The magnificent wood carving of the Urnes Stave Church, from which the style takes its name, comes to mind when recalling great examples of this style. The carvings come from an earlier church built on the site, and were reused in the current surviving iteration of the stave church.

Distribution

The Urnes style is found throughout Scandinavia and the Norse settlements around Europe, and like the Ringerike style, it was partly adopted in Ireland and persisted there, even when its popularity had faded in contemporary Scandinavia.

Romanesque Art

In Norse regions, the Urnes style transitioned to, and blended with the contemporary Romanesque art, which dominated Christian European culture.

Examples

Examples on Gelmir.com →

A list of examples with photos, info and links to sources.

Dateable

c. 1050

Fluted silver bowl

— the Lilla Valla Hoard

Lilla Valla, Gotland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 112973.

(c. 1075)

The Urnes Church Wood Carvings

Urnes, Sogn og Fjordane, Norway.

c. 1070

The Hørning Beam

Hørning, Jylland, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, D2309.

c. 1100 – 1150

Wood carving from furniture

Trondheim, Trøndelag, Norway.

NTNU Vitenskabsmuseet Trondheim, N30000.

Undateable

Animal Head — Gotland *

Gotland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 108125.

Bird-shaped brooch — Gresli *

Gresli Nordre, Trøndelag, Norway.

NTNU Vitenskapsmuseet, Trondheim, T2042.

Bird-shaped brooch — Spejlsgårde *

Spejlsgårde, Fyn, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, 493580.

Bird-shaped brooch — Toftegård *

Toftegård, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, 4036.

Box-shaped brooch

Tjängdarve, Träkumla, Gotland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 449041.

Crucifix — Bonderup *

Bonderup, Sjælland, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, 32222.

Crucifix — Gåtebo

Gåtebo, Öland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 41379.

Crucifix — Orø *

Næsby, Orø, Sjælland, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, 46215.

Crucifix — Østermarie *

Østermarie, Bornholm, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, D74/2013.

Crucifix Chain — Østermarie *

Østermarie, Bornholm, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, D228/2013.

Crucifix Chain Terminals — Østermarie *

Østermarie, Bornholm, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, D76/2013; D77/2013.

Crucifix — Vestlolland *

Vestlolland, Lolland, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, Købenahavn, D 474/1994.

Head of a tau crozier

Þingvellir, Iceland.

Þjóðminjasafn Íslands, Reykjavík, 15776.

Openwork brooch — Bejsebakken *

Bejsebakken, Aalborg, Jylland, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, C30567.

Openwork Brooch — Bøe *

Bøe, Innlandet, Norway.

Universitetets Oldsaksamling, Oslo, C27822.

Openwork Brooch — Eriksmyr *

Eriksmyr, Vestfold og Telemark, Norway.

Universitetets Oldsaksamling, Oslo, C28696.

Openwork Brooch — Erritsø *

Erritsø, Jylland, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, C30312.

Openwork Brooch — Haug *

Haug, Viken, Norway.

Universitetets Oldsaksamling, Oslo, C59331.

Openwork Brooch — Hestehagen *

Hestehagen, Viken, Norway.

Universitetets Oldsaksamling, Oslo, C14077.

Openwork Brooch — Kiaby *

Kiaby, Skåne, Sweden.

The British Museum, London, 1982,0602.1.

Openwork brooch — Lindholm Høje

Lindholm Høje, Jutland, Denmark.

Nationalmuseet, København, ÅHM1937.

Openwork Brooch — Oslogate *

Oslogate, Oslo, Norway.

Universitetets Oldsaksamling, Oslo, C37175.

Openwork brooch — Tröllaskógur

Tröllaskógur, Suðurland, Iceland.

Þjóðminjasafn Íslands, Reykjavík, 6524.

Openwork brooch — Östervärv

Östervarv, Östergötland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 457409.

Runestone G 114 II

Ardre, Gotland, Sweden.

Runestone G 114 VI

Ardre, Gotland, Sweden.

Runestone G 114 I

Ardre, Gotland, Sweden.

Runestone G 114 V

Ardre, Gotland, Sweden.

Runestone U 130

Nora, Uppland, Sweden.

Runestone U 460

Skråmsta, Uppland, Sweden.

Woodcarving — Hemse *

Hemse, Gotland, Sweden.

Historiska Museet, Stockholm, 858388.

* Examples added to the list in 2023.

Runestones

Runestone Style Pr 3 (Early Urnes Style)

Runestone Style Pr 4 (Urnes Style Proper)

Runestone Style Pr 5 (Late Urnes Style)

Examples removed from the list in 2023

- Box tomb in Vreta Monastery. Vreta, Östergötland, Sweden.

- Runestone U 177. Stav, Uppland, Sweden.

- Runestone U 202. Vallentuna, Uppland, Sweden.

- Runestone U 961. Vaksala, Uppland, Sweden.

- Runestone Sö 276. Strängnäs, Södermanland, Sweden.

Litterature

Graham-Campbell, James, 2013. Viking Art.

Fuglesang, Signe Horn, 1980. Some Aspects of the Ringerike Style.

Fuglesang, Signe Horn, 1981. ‘Stylistic Groups in Late Viking and Early Romanesque Art.’ Acta ad Archaeologiam et Artium Historiam Pertinentia (Series altera in 8°) 79–125.

Anne-Sofie Gräslund, 2001. Dating the Swedish Viking-Age rune stones on stylistic grounds.