The Ingvar Expedition

December 17, 2019

In the same series:

The Runestone Styles

The Styles

The Stones

- The Hunnestad Monument

- The Eastern Route Stones

- The Ingvar Stones

- The Broby Stones

- The Sigurd Stones

Introduction

Few hard facts about Ingvar the Far-Travelled and his expedition are known. But what is certain is that a man called Ingvar led a large expedition containing a sizeable number of ships, from the area around Lake Mälaren in Sweden, going down the Eastern trading routes of Europe.

The expedition began sometime in the second half of the 1030s and ended in the early 1040s. It was the last major Swedish viking expedition.

Ingvar and his retinue perished somewhere in the East and very few if any of the members of the company survived the journey.

The catastrophic end of the expedition impacted the Swedish community profoundly, which is reflected in the large number of runestones raised to commemorate the participants of the event compared to other similar expeditions to England.

The mysterious and tragic fate of the expedition gave inspiration to heroic legends about Ingvar among his contemporaries. Ingvar’s saga was later written down more than two centuries after the expedition took place by the monk Oddr Snorrason in his largely fictional and rather fantastical retelling of the Saga of Yngvar the Far-Travelled.

Ingvar

Ingvar the Far-Travelled (Old Norse: Yngvarr Víðförli) must have been at least a ‘magnate’ or a chieftain, and he probably originates from the Strängnäs area around Mälaren in Sweden.

An expedition the size of Ingvar’s must have been authorised by the Swedish king, which at the time was Anund Jakob, who was the grandson of King Erik the Victorious (Old Norse: Eiríkr inn sigrsæli). Ingvar might also have been related to King Erik. At least according to Ingvar’s saga, he was the great-grandson of Erik, but this is questionable and can not be verified in other sources.

The Expedition

Several scholars have made attempts at reconstructing the journey of Ingvar and his retinue, but none of them has been convincing.

The Saga of Yngvar the Far-Travelled describes the journey of Ingvar and his retinue in detail. But apart from the first part of the saga situated in Sweden and Garðaríki (probably the Kyivan Rus Kingdom) describing Ingvar’s genealogy and his close connections to the Swedish royal family and a Rus king, the rest of the saga describing the journey can not be connected convincingly to historical or geographical facts and seems to be heavily inspired by motifs of popular oral and literary traditions.

Ingvar and his retinue are not mentioned in any reliable Eastern source. Although Norse activity in the East is mentioned in sources like the Russian Primary Chronicle (twelfth century) and the Gregorian Chronicle, none of the events described in the chronicles can be linked directly to the expedition other than to reconfirm that a Norse endeavour like Ingvar’s taking place is in fact absolutely plausible.

The many runestones raised in Sweden commemorating family members taking part in the expedition paint a faint but cohesive picture. From the inscriptions, we can conclude that many followed Ingvar on ships in the East where they fought and won battles but ultimately met their fate in ‘Serkland’.

The meaning of Serkland is not clear. It is probably the land of the Saracens, i.e. the Arab and geographically the area around and between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea. But it might also just be a term for an exotic faraway place as it is used in the legendary sagas.

The Ingvar Runestones

About thirty commemorative runestones, located in the area around Lake Mälaren, testify to the existence of the expedition and its leader Ingvar. This makes the Ingvar expedition the most mentioned single event on runestones, only surpassed in number by the c. thirty Greece runestones and c. thirty England runestones.

The inscription on an Ingvar stone usually states the name of the one(s) who raised the memorial followed by the name of the relative commemorated, typically with the addition of the statement that they “travelled to the East with Ingvar” or “fell in the East with Ingvar”. A few stones mention “Serkland” as the final and fatal destination of the travellers. Occasionally the inscriptions also state that the dead “owned a ship”, “was a good sailor” or that they fought and won battles.

Examples

Below are a selection of typical and notable Ingvar stones inscriptions.

Sö 107

“Hróðleifr raised this stone in memory of his father Skarfr. He travelled with Ingvarr.”

Sö 131

“Spjóti (and) Halfdan, they raised this stone in memory of Skarði, their brother. From here (he) travelled to the east with Ingvarr; in Serkland lies Eyvindr’s son.”

U 644

“Andvéttr and and Kárr and Blesi and Djarfr, they raised this stone in memory of Gunnleifr, their father. He fell in the east with Ingvarr. May God help (his) spirit.”

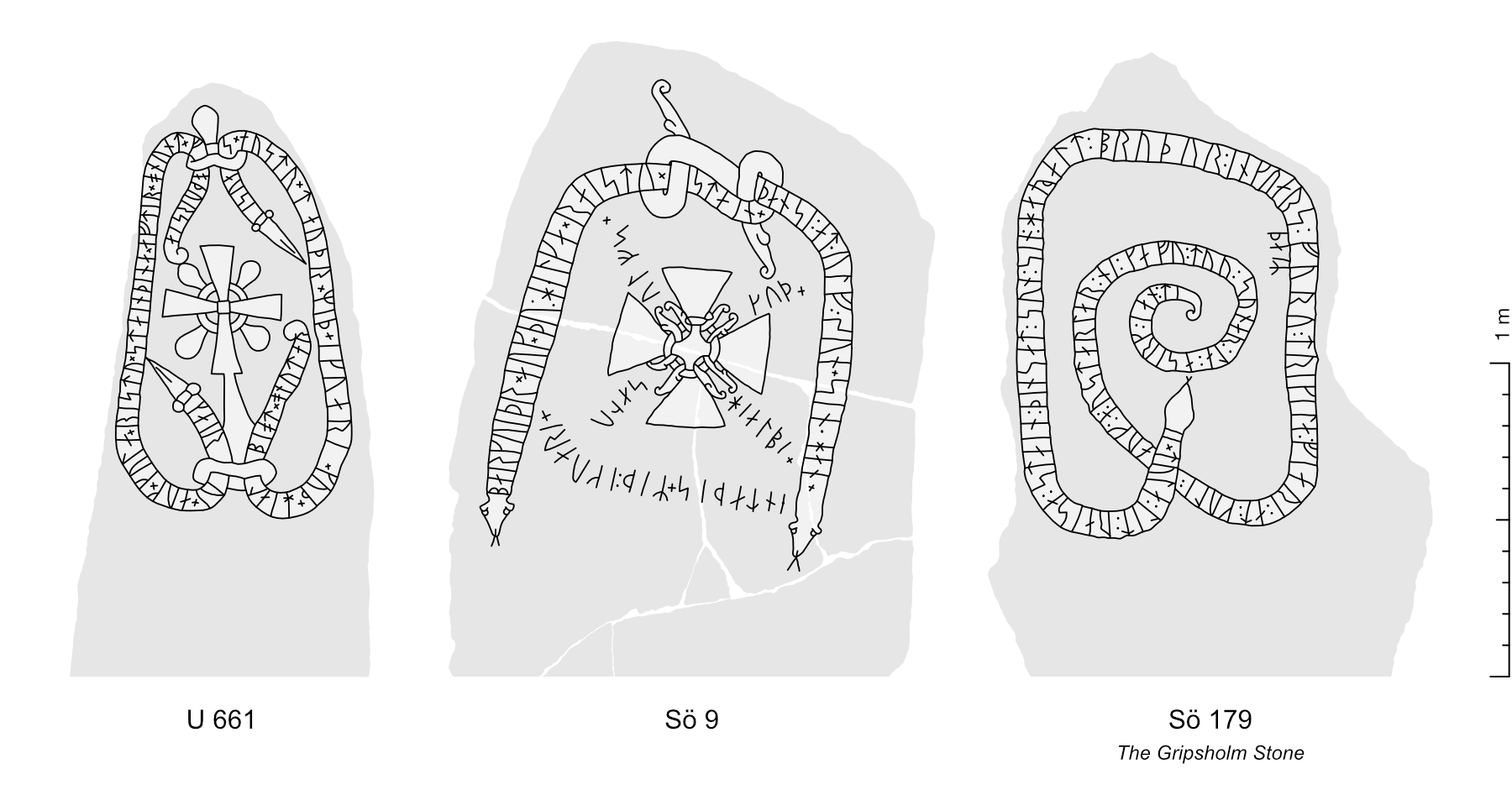

Sö 9

“Bergviðr/Barkviðr and Helga, they raised this stone in memory of Ulfr, their son. He met his end with Ingvarr. May God help Ulfr’s soul.”

U 778

“Þjalfi and Holmlaug had all of these stones raised in memory of Banki/Baggi, their son, who alone owned a ship and steered to the east in Ingvarr’s retinue. May God help Banki’s/Baggi’s spirit. Áskell carved.”

U 654

“Andvéttr and Kárr and and Blesi and Djarfr raised this stone in memory of Gunnleifr, their father, who was killed in the east with Ingvarr. May God help their spirits. Alríkr(?), I carved the runes. He (Gunnleifr) could steer a cargo-ship well.”

Sö 179

“Tóla had this stone raised in memory of her son Haraldr, Ingvarr’s brother.

They travelled valiantly

far for gold,

and in the east

gave (food) to the eagle.

(They) died in the south

in Serkland.”

Classification

In some cases, it can be difficult to establish if a stone belongs to the group of Ingvar stones. The inscription can be damaged and missing crucial information, the inscription can be ambiguous and difficult to interpret, or the information can be too vague to connect it to the Ingvar expedition reliably. Based on these varying conditions, the stones can be categorised in the following four groups:

Group 1 — Certain Ingvar Runestones (21 stones)

Stones which fully comply with the defined criteria of the group:

Sö 9. Lifsinge, Dillnäs sn, Daga hd.

Sö 105. Högstena, Kjula sn, Öster Rekarne hd.

Sö 107. Balsta, Klosters sn, Öster Rekarne hd.

Sö 108. Gredby, Klosters sn, Öster Rekarne hd. (now Eskilstuna).

Sö 131. Lundby, Lids sn, Rönö hd.

Sö 173. Tystberga, Tystberga sn, Rönö hd

Sö 179. Gripsholm, Kärnbo sn, Selebo hd.

Sö 254. Vansta, Ösmo sn, Sotholms hd.

Sö 281. Strängnäs, Domkyrkan.

Sö 287. Hunhammar (now Norsborg), Botkyrka sn, Svartlösa hd.

Sö 320. Stäringe, Årdala sn, Villåttinge hd.

Sö 335. Ärja ödekyrka, Åkers sn, Åkers hd.

U 439. Steninge, Husby-Ärlinghundra sn.

U 644. Ekilla bro, Yttergrans sn.

U 654. Varpsund, Vi ägor, Övergrans sn.

U 661. Råby, Håtuna sn.

U 778. Svinnegarns kyrka.

U 1143. Tierps kyrka.

U Fv1992;157. Husby-Ärlinghundra s:n, Arlanda, Måby ägor.

Vs 19. Berga, Skultuna sn. Now at Skultuna bruk.

Ög 155. “Sylten”, Bjällbrunna ägor, Styrstads sn, Lösings hd

Group 2 — Probable Ingvar Runestones (3 stones)

Stones which contain strong indications of belonging to the group but don’t fully comply with the defined criteria:

M 4. “Lilla Attmarsstenen”, Attmars kyrka, Attmars sn.

Sö 277. Strängnäs, Domkyrkan.

Sö 360. Bjuddby, Blacksta sn, Oppunda hd.

Group 3 — Possible Ingvar Runestones (2 stones)

Stones without strong indications of belonging to the group, but also not possible to completely exclude:

Sö 279. Strängnäs, vid Domkyrkan.

U 785. Tillinge kyrka.

Group 4 — Other runestones of interest to the Ingvar group (8 stones)

Other stones which are of high interest to the group in various degrees:

Sö 96. Jäders kyrka, Östra Rekarne hd.

Sö 278. Strängnäs, Domkyrkan.

U 513. Rimbo kyrka.

U 540. Husby-Lyhundra kyrka.

U 837. Alsta, Nysätra sn.

Vs 1. Stora Rytterns kyrkoruin, Rytterns sn.

Ög 30. Skjorstad, Tåby sn, Björkekinds hd.

Ög 145. Dagsberg, kyrkogårdsmuren, Lösings hd.

Ingvar’s Saga

The Saga of Yngvar the Far-Travelled (Old Norse: Yngvars saga víðförla) is classified as a legendary saga (Icelandic: fornaldarsaga) and postclassical fiction. But unlike other legendary sagas, it claims to be an account of actual events even though it is a strange mixture of history and myth, Latin clerical learning and Old Norse folklore.

An English translation of the full saga can be found online here:

Tunstall, Peter (2005). The Saga of Yngvar the Traveller

Summary

The narrative can be divided into three main parts and a final chapter describing the author’s sources for the saga.

The first part describes Yngvar’s royal origin and his ability to prove and conduct himself as a competent prospective king and explores his motivation to seek out a kingdom outside of Sweden when his ambitions outgrow his opportunities under the Swedish king.

The second part describes Yngvar’s expedition to seek out a kingdom for himself in which he and his crew travels down a major river through Eastern Europe encountering many mystical and mythical obstacles along the way. Yngvar is presented as a paragon of Christian virtue, and he often warns the members of the expedition not to engage with the heathens and their activities. When they do anyways, they become sick or die. Before most of the crew, including Yngvar, eventually succumbs to a mystical disease he promises queen Silkisif to return to her city Scythopolis and convert her and her people.

The third part describes how Yngvars’s son Svein travels to Scythopolis to keep Yngvar’s promise to convert Silkisif and her people. She marries him, and Svein is crowned king of her lands. Svein brings with him a Swedish bishop to help with the conversion and builds a church dedicated to his father, Yngvar.

Narrative Motifs

Some of the folkloristic motifs of the obstacles both Yngvar and his son Svein encounter along the Eastern route are from Classical mythology and may be traced back to Medieval Latin authorities like Isidore of Seville. Two cities, Heliopolis and Scythopolis, both have Greek names, a dragon by the name Jaculus has been fetched from Lucan’s Pharsalia and other motifs like birdmen, a cyclops and dangerous ‘Amazonian’ women are also well-known motifs.

The story of Silkisif’s conversion and the building of Yngvar’s church in Scythopolis has a hagiographic touch typical of medieval religious literature. Hagiography meaning idealised biographies of saints or ecclesiastical leaders.

Background

The saga was written down sometime in the late 12th century by Oddr Snorrason, who was a monk at the Þingeyrar monastery in Iceland and also the author of a Latin biography of King Olav Tryggvason.

He based his account of Ingvar’s expedition on oral traditions that, to some extent, can be traced back to Sweden and the time of Ingvar the Far-Travelled.

The text is preserved in two late Icelandic medieval vellum manuscripts: Gl. Kgl. Sml. 2845 4° and AM 343a 4° dating from the fifteenth century which are both based on the original chronicle written by Oddr.

The Political Climate

At the time when Oddr wrote down the saga, there was a major political conflict in Europe concerning the power of the Church. The so-called ‘sacerdotium’ consisting of the papacy and bishops loyal to the pope argued in favour of making the church completely independent of secular power. But the ‘regnum’ consisting of secular kings and leaders wanted to remain in control of the churches.

Oddr and the Þingeyrar monastery supported the regnum, as well as king Sverrir of Norway. As did Gizurr Hallson and Jón Loftsson, who were the two most important chieftains in Iceland and church leaders towards the end of the twelfth century. Gizurr and Jón were probably the ones responsible for commissioning Oddr to write his version of Ingvar’s Saga.

In line with the political agenda of the regnum, the obvious political goal of Oddr’s version of the saga is to promote that great and pious secular leaders could be considered holy men even though they were not known to have worked miracles and that they, therefore, should have an important say in ecclesiastical matters.

The saga portrays Ingvar as a Christian missionary of royal descent and in that respect similar to Olav Tryggvason and the story contains motifs similar to hagiographic literature.

Origin and Development

The portrayal of Garða-Ketill’s role in the saga as a first-hand source and reporter of the events is highly questionable. No such person is known from other Icelandic sources, and his character and name feel like a narrative construct. The name Ketill translates to ‘cauldron’, which is the exact item he happens to steal from the giant in the saga.

The early existence in both Sweden and Iceland of oral traditions about Ingvar’s expedition is well reflected on the Gripsholm stone (Sö 179). The second half of the inscription on the runestone commemorating a member of Ingvar’s retinue is in alliterative verse of the form fornyrðislag, which suggest that poetry composed to retell the story of Ingvar’s journey was already well-known shortly after the dire fate of the expedition in the early 1040s.

The early versions were probably originally first and foremost about adventurous vikings seeking fortune and fighting battles in the East. The Christians who erected the stones believed that malevolent heathen forces in some faraway country had somehow destroyed the expedition.

As the legend grew, motifs of other stories got incorporated such as Old Norse mythology, legendary sagas, stories of other princes who travelled abroad and perished (also known by Adam of Bremen), classical myths and edifying stories.

The saga was probably later adopted by the clerics and turned into the hagiographic story we know today of a missionary and his crew delivered to us in written form by Oddr.

Litterature

Lönnroth, Lars. (2014) From History to Myth: The Ingvar Stones and Yngvars saga viðfǫrla.

Thunberg, Carl L. (2010). Ingvarståget och dess monument. En studie av en runstensgrupp med förslag till ny gruppering.

The Scandinavian Runic-text Data Base.

Sveriges runinskrifter.

Tunstall, Peter (2005). The Saga of Yngvar the Traveller.