The Eastern Route Stones

March 14, 2023

In the same series:

The Runestone Styles

The Styles

The Stones

- The Hunnestad Monument

- The Eastern Route Stones

- The Broby Stones

- The Sigurd Stones

Introduction

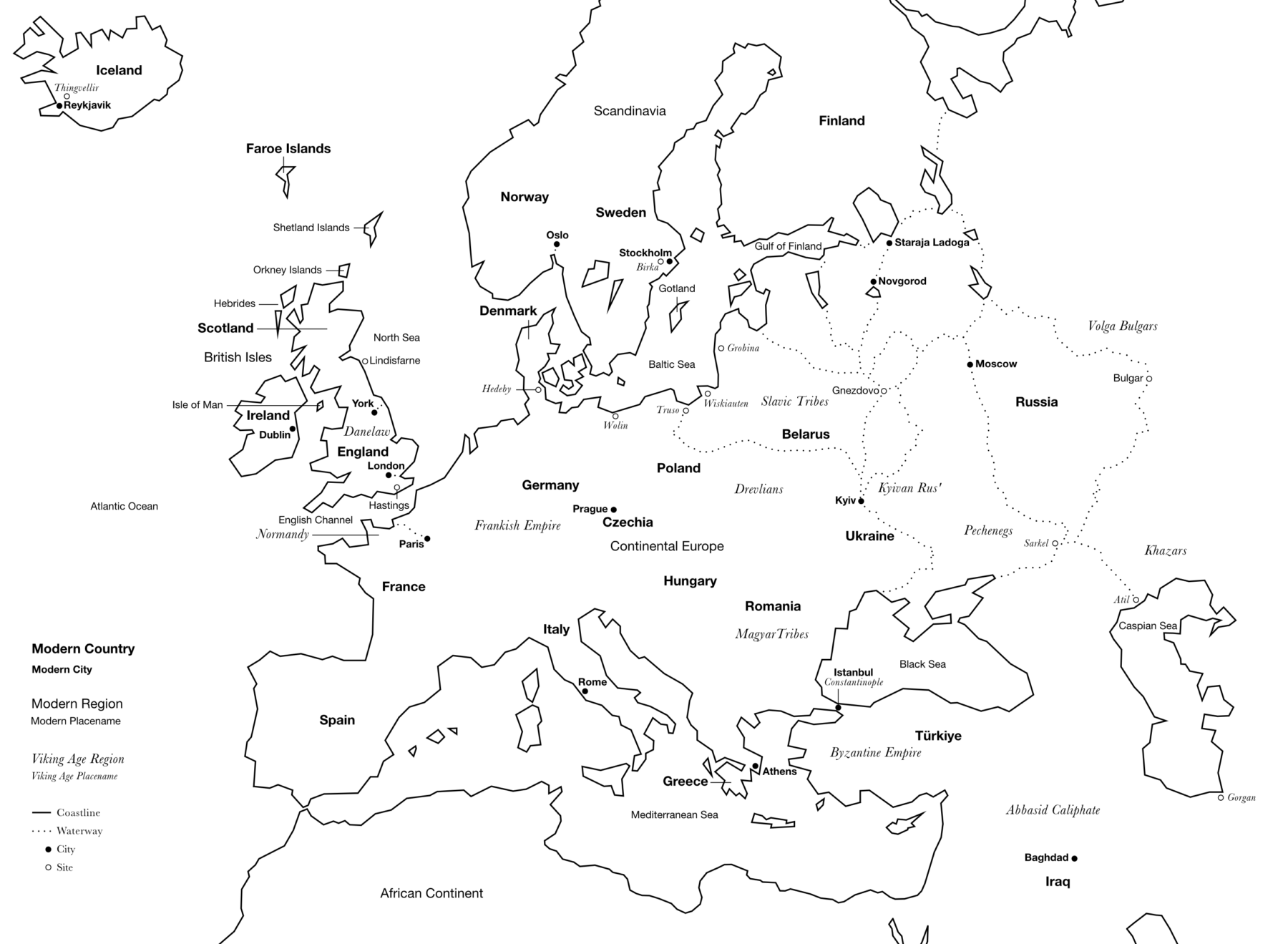

Several runestones refer to Scandinavian expeditions to the East (Old Norse: Austr), the Eastern Way (Old Norse: Austrvegr), or to eastern locales like Garðar (probably the territory of the Kyivan Rus’) and Holmgarðr (Novgorod). On other runestones, journeys to Grikkium (Greece) and Langbarðalandi are mentioned (Lombardy, Italy).

Another related group of stones is the Ingvar stones, all raised in memory of or in relation to a sizable company of men who travelled with Ingvar from Sweden and died with him somewhere far along the Eastern route.

Ingvar might have reached as far as Serkland (probably the land of the Saracens south of the Caspian Sea), a destination mentioned on some stones too.

In addition to the Scandinavian stones, runic inscriptions by Scandinavian travellers are known from the Eastern route itself too, like the Berezan’ runestone in Ukraine and the runic inscriptions in the Hagia Sophia cathedral (Istanbul, Türkiye) as well as the one decorating the Piraeus Lion (originally Greece, now Venice, Italy).

Virtually all of the runestones were raised during the Christianization of Scandinavia in the 11th century, well after the establishment of the Kyivan Rus’ state on the Eastern route and when the Scandinavians had strong relations with the Rus’ ruling family.

The Eastern Route

Silver in the shape of Arabic dirhems from the Muslim Abbasid Caliphate was a sought-after import commodity in Scandinavia.

Scandinavian merchants sought eastward to exchange goods like heather, wool and silk, fur, iron, wax, and tar, as well as animals and enslaved humans, in return for especially silver.

The hunger for enslaved people was especially significant in the capital cities of the Caliphate, Baghdad, and the Eastern Roman Empire, Constantinople (ON: Miklagarðr), and the Scandinavians were more than ready to supply.

Birka and Gotland

For Scandinavians heading east, Birka in modern-day Stockholm, Sweden, and the island of Gotland, located in the middle of the Baltic Sea, were popular vantage points.

The Baltic Sea

Several trade stations and towns manifested along the coast of the Baltic Sea in northern Continental Europe, like Haithabu in contemporary north Germany, and further east, Wolin, Truso and Wiskiauten (Poland), as well as Grobina (Latvia).

Staraja Ladoga

Europe’s largest freshwater lake, Ladoga (Russia), became the primary entryway into Eastern Europe as the gateway to the Volkov river via the settlement Staraja Ladoga, a crucial trading post for the Scandinavian fur (in particular hare and lemming) to the Califate.

The Dnipro River

One route eastward went south through Holmgarðr (Novgorod) and Gnezdovo before passing through Kyiv on the Dnipro River and then entering the Black Sea, where Constantinople, the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire, was located on the opposite southern coast.

The Volga River

Another route went along the Volga river via Bulgar to two essential trading posts for enslaved people to the Caliphate, the Khazar towns Sarkel and Atil. The latter was located on the coast of the Caspian Sea, with Baghdad reachable by land from the southern coast of the sea via Gorgan.

The Kyivan Rus’

Around 800, a settlement of a mixture of Finns, East Slavs, Baltics, and Scandinavians emerged at Staraja Ladoga.

From this settlement and under the strong Scandinavian influence, Rus’ gradual expansion of the control of the Slavic regions along the Eastern route’s rivers developed in the ninth and tenth century into the Kievan Rus’, the first state to arise among the Eastern Slavs and the seat of the Kyivan grand prince from about 880.

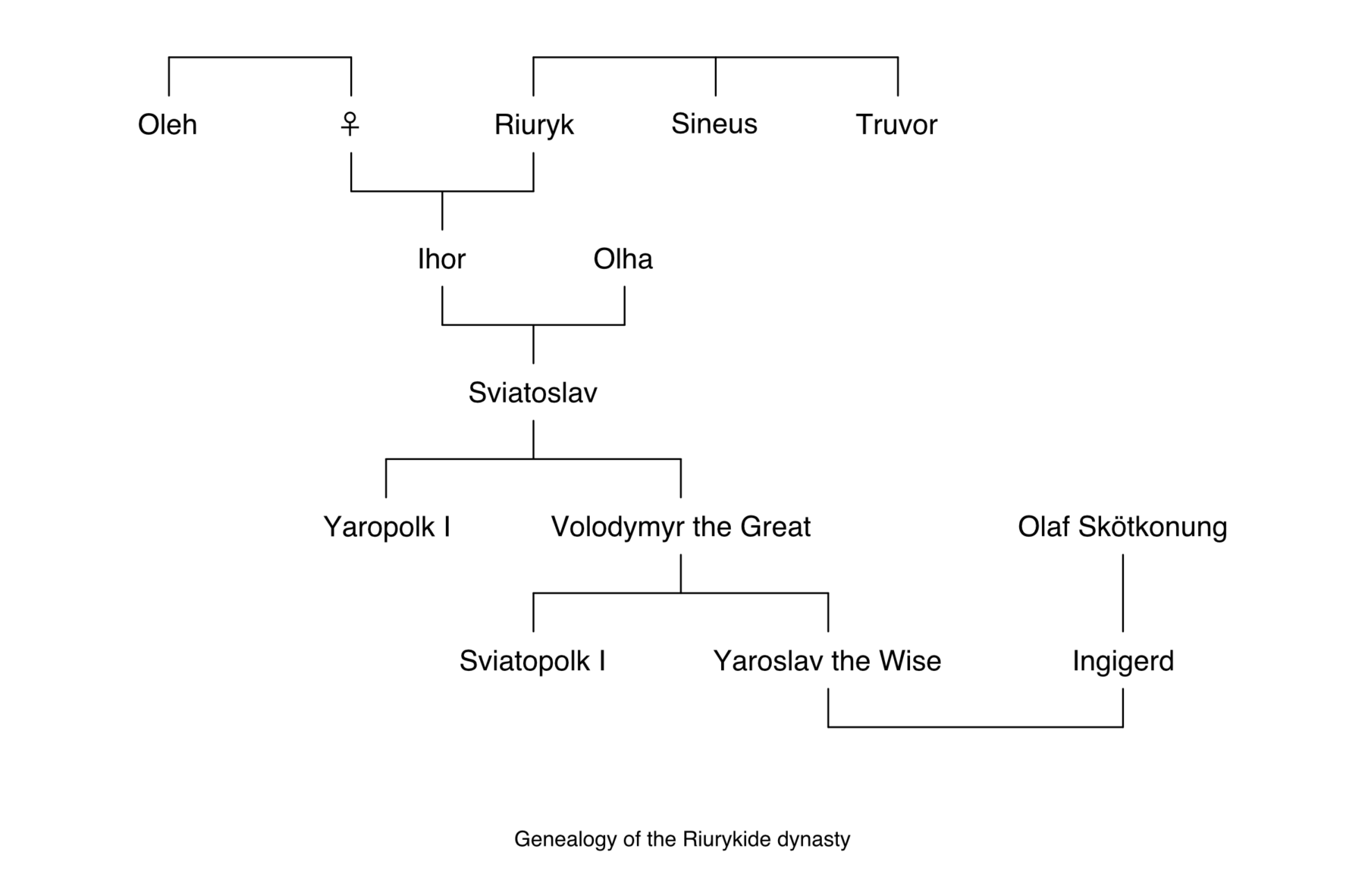

Riuryk (?-879) and the Riurykide dynasty

According to Nestor’s Chronicle (12th century), in 862, three Rus’ brothers, Riuryk (ON: Hrøríkʀ), Sineus and Truvor, were invited to rule the territories of Novgorod, Beloozero and Izborsk, respectively. The brothers tightened control of the rivers’ northern reaches, built fortifications and collected taxes from the Slavic tribes. Two years later, Riuryk’s brothers were both dead, and he took control of their territories.

Prince Oleh (?-912/922)

When Riuryk died in 879, power was formally transferred to his minor son Ihor (ON: Ingvar) but in practice to Ihor’s maternal uncle Oleh (ON: Helgi).

According to the chronicle, Oleh sailed down the Dnipro River the same year with a fleet capturing Kyiv. He then moved the capital from Novgorod to Kyiv, establishing the Kyivan Rus’. He successfully extended his control over several more tribes and ended the Khazar’s domination in the region.

In 907, Oleh allegedly gathered an enormous fleet and launched a successful surprise attack on the Eastern Roman Empire by sailing across the Black Sea and directly into the otherwise well-guarded harbour of Constantinople. Oleh negotiated a favourable treaty with the emperor, giving Kyivan Rus’ merchants extensive commercial privileges in the Empire, including the slave market in Constantinople. The treaty’s conditions also allowed the Rus’ to serve in the Emperor’s personal guard, the Varangian Guard.

Prince Ihor (c. 877-945)

Grand prince 912-945.

Ihor expanded the Kyivan Rus’ territory during his reign, subjugating more Slavic tribes.

As the East Roman fleet was engaged in war with the Caliphate and the Bulgars in 941, Ihor attacked Constantinople. Nonetheless, he gained a devastating defeat by the returning Roman fleet repelling his army with ‘Greek fire’.

Ihor rebuilt his army in the following years. Still, before he got the chance to attack again, the emperor sent representatives to Kyiv, negotiating a favourable treaty in 944 on the condition that he would refrain from attacking Roman provinces.

Ihor rebuilt his army in the following years. But, before he launched another offensive, the emperor sent representatives to Kyiv to negotiate a favourable treaty in 944 on the condition that Ihor would refrain from attacking Roman provinces.

He was killed in 945 by Derevlianians while attempting to collect excessive tribute.

Princess Olha (c. 890-969)

Sviatoslav’s regent during his minority 945-957 and his later military campaigns.

Ihor’s death was avenged by his widow, princess Olha (ON: Helga), who subdued the Derevlianians. However, Olha prioritised trade over war, enhancing the commercial network and reforming tax collection during her reign.

In 957, Olha went on a diplomatic trip to Constantinople, returning home a Christian woman with favourable trade agreements. She was the first Rus’ ruler to convert to Christianity and to establish direct ties with central and western-European rulers.

Her grandson Volodymyr the Great had her remains reburied in Kyiv’s Church of the Tithes, and she was later canonised during the first half of the 13th century.

Sviatoslav I Ihorovych (942?-972)

Grand prince 945/964-972.

Olha’s son, Sviatoslav, on the other hand, expanded the territory to the east in 965 through violence. He sacked and burned the Khazar’s capital, Atil, after a series of attacks on Muslim trading posts along the coast of the Caspian Sea.

Encouraged by the Eastern Roman emperor, Sviatoslav conquered the Bulgars in 968. As the Emperor turned against him in 969, he threatened Constantinople by launching a campaign in the Balkans. Yet in 971, under siege from the Eastern Roman army, he was compelled to accept a peace agreement.

The name ‘Halfdan’ is mentioned in the contract between Constantine VII and Sviatoslav; the same name appears in a runic inscription in Hagia Sophia.

On his way back to Kyiv, Sviatoslav was ambushed by Pechenegs orchestrated by Constantinople, which led to the destruction of his army and his death.

Volodymyr the Great (c. 956-1015)

Grand prince 980-1015.

After his brother, the grand prince of Kyiv, Yaropolk I, forced him to flee to Scandinavia, Volodymyr (ON: Valdamarr) returned and captured Kyiv in 980.

He expanded and consolidated the Kyivan Rus’ into one of the most powerful states in Eastern Europe.

Following Volodymyr’s conversion and marriage to Anna Porphyrogeneta (963–1011), sister of the emperor Basil II, an ecclesiastical network staffed by Roman clergy was established in the Kievan Rus’. Long before their Scandinavian compatriots, Varangian soldiers were baptised in Hagia Sophia.

Volodymyr the Great brought Rus’ political unity through organised religion. The acceptance of Christianity as the state religion facilitated the unification of the Rus tribes and the development of dynastic, political, cultural, religious, and commercial ties with other countries, particularly with the Eastern Roman Empire, Bulgaria, and Germany.

Volodymyr died in 1015 and was buried in the Church of the Tithes. He was canonised after 1240.

Yaroslav the Wise (978-1054)

Grand prince 1036–54.

After Volodymir’s death, his son Yaroslav the Wise captured Kyiv by defeating his brother Sviatopolk I.

Yaroslav’s codification of the law and territorial expansions significantly aided the internal consolidation process that had already begun.

The cities of Kyiv, Novgorod, Chernihiv, Pereiaslav, Volodymyr-Volynskyi, and Turiv underwent significant change during Yaroslav’s rule. In Kyiv alone, more than 400 churches were constructed, including the Saint Sophia Cathedral, making it a contender to Constantinople in terms of architecture.

Yaroslav also strengthened the international role of Kyivan Rus’ through dynastic unions. He married Ingigerd (1001-1050), later known as Saint Anna, the daughter of King Olaf Skötkonung of Sweden, and arranged marriages for his daughters and sons into the western-European royal elite.

Yaroslav’s court also granted asylum to the monarchs Olaf II Haraldsson, Harald III of Norway, and Edmund II Ironsides of England.

Yaroslav died in 1054 and was buried in the Saint Sophia Cathedral.

The Runetones

Mentions of ‘the East’

Twenty-one Scandinavian runestones mention men who had been in the east: DR 108, Sö 33, Sö 92, Sö 121, Sö 126, Sö 130, Sö 216, Sö 308, Sö 338, U 153, U 154, U 283, U 504, U 636, U 898, Vg 184, Vg 197, Vs 1, Vs Fv1988;36, Ög 8 and Ög 30. In addition, two stones mention Scandinavians travelling along the eastern route: U 366 and Vg 135.

Examples:

Vg 184

“Gulli/Kolli raised this stone in memory of his wife’s brothers Ásbjǫrn and Juli, very good valiant men. And they died in the east in the retinue.”

Sö 34

“Styrlaugr and Holmr

raised the stones,

in memory of their brothers,

next to the path.

They met their end

on the eastern route,

Thorkell and Styrbjǫrn,

good Thegns.”

Sö 126

“Holmfríðr (and) (?), they had the stone cut in memory of Áskell, their father.

He engaged in battle

on the eastern route,

before the people’s commander

wrought his fall.”

Mentions of ‘Garðar’

Eight Scandinavian runestones mention men who had been in Garðar: G 114 II, N 62, Sö 148, Sö 338, U 209, U 636, Vs 1 and Öl 28.

‘Garðar’ is an Old Norse term referring to the Rus’ regions east of Scandinavia.

The plural term ‘garðar’ means fences or fortifications and was probably a name derived from the collective of fortified settlements along the eastern European rivers from the Baltic Sea and Staraja Ladoga towards the Black Sea, approximately equivalent to the territory of the Kyivan Rus’.

The term ‘Garðaríki’, adding the suffix ‘realm’ to the term, appeared in the twelfth century and could thus be interpreted as ‘the land of fortifications’.

Examples:

Sö 130

“Four (sons) made the magnificence

in memory of (their) good father,

valiantly

in memory of Dómari/the judge,

gentle in speech

and free with food …

He fell in Garðar …”

Sö 338

”Ketill and Bjǫrn, they raised this stone in memory of Thorsteinn, their father; Ônundr in memory of his brother and the housecarls in memory of the just (?) (and) Ketiley in memory of her husbandman.

These brothers

were the best of men

in the land

and abroad in the retinue,

held their

housecarls well.

He fell in battle in the east

in Garðar,

commander of the retinue,

the best of lanðolders.”

Mentions of ‘Holmgarðir’

Three Scandinavian runestones mention men who had been in Holmgarðir: G 220, Sö 171 and U 687.

Holmgarðir was the Old Norse name for Novgorod, a compound noun meaning ‘island enclosure’ or ‘fortified island’.

Examples:

Sö 171

“Ingifastr had the stone cut in memory of Sigviðr, his father.

He fell

in Holmgarðr,

the ship’s leader

with the seamen.”

U 687

“Rúna had the landmark made in memory of Spjallboði and in memory of Sveinn and in memory of Andvéttr and in memory of Ragnarr, sons of her and Helgi/Egli/Engli; and Sigríðr in memory of Spjallboði, her husbandman. He died in Holmgarðr in Ólafr’s church. Œpir carved the runes.”

A Scandinavian stone in Kyivan Rus’

In addition to the stones in Scandinavia, a runestone has been found on the Berezan’ island in southern Ukraine.

The Berezan’ island is located in the Black Sea at the mouth of the Dnipro River, and thus right on the eastern trade route from Scandinavia, through Kyiv, to Constantinople.

The shape of the stone is reminiscent of the slabs used in stone sarcophaguses on Gotland, and the inscription of the Old Norse word ‘hvalf’ (vault, coffin) also hints at this Gotlandic tradition.

Runic inscriptions in Hagia Sophia

At least three runic texts exist among the many graffiti inscriptions in Hagia Sophia.

While now a mosque, Hagia Sophia was the most significant Christian cathedral of the Eastern Roman Empire, located in Constantinople.

The inscriptions are generally tough to decipher as they are worn and vague. Dating is difficult too, but they were most likely produced c. 1050-1150 and were most likely carved by Scandinavian mercenaries in the emperor’s service.

All three known inscriptions in English:

“Halftan …”

“Arni”

“Arinbárðr cut these runes”

The Stones and Inscriptions

Türkiye

The Hagia Sophia Inscriptions. Hagia Sophia, Istanbul, Türkiye.

Ukraine

UA Fv1914;47. Berezan’ Island, Mykolaiv Oblast, Ukraine (now Odesa Archeological Museum, Одеський археологічний музей)

Denmark

DR 108. Kolind, Djursland, Denmark.

Norway

N 62. Alstad, Toten, Oppland, Norway (now Kulturhistorisk Museum, Oslo).

Gotland, Sweden

G 114 II (G 114 I, G114 V, G 114 VI). Ardre, Gotland, Sweden.

G 134 (G 135). Sjonhems, Gotland, Sweden (now Gotlands fornsal, Visby).

G 220. Hallfrede, Gotland, Sweden (fragment, now ‘Gotlands Fornsal’).

G 280. Pilgårds, Gotland, Sweden.

Södermanland, Sweden

Sö 33. Skåäng, Södermanland, Sweden.

Sö 34. Tjuvstigen, Södermanland, Sweden.

Sö 92. Husby, Södermanland, Sweden

Sö 121. Bönestad, Södermanland, Sweden (now lost).

Sö 126. Fagerlöt, Södermanland, Sweden.

Sö 130. Hagstugan, Södermanland, Sweden.

Sö 148. Innberga, Södermanland, Sweden.

Sö 171. Esta, Södermanland, Sweden.

Sö 216. Aska, Södermanland, Sweden (fragments, now lost).

Sö 308. Södertälje, Södermanland, Sweden.

Sö 338. Turinge, Södermanland, Sweden.

Uppland, Sweden

U 153. Lissby, Uppland, Sweden.

U 154. Lissby, Uppland, Sweden.

U 209. Veda, Uppland, Sweden.

U 283. Torsåker, Uppland, Sweden.

U 366. Gådersta, Uppland, Sweden (fragment, now lost).

U 504. Ubby, Uppland, Sweden.

U 636. Låddersta, Uppland, Sweden.

U 687. Sjusta, Uppland, Sweden.

U 898. Norby, Uppland, Sweden.

Västergötland, Sweden

Vg 135. Hassla by, Västergötland, Sweden.

Vg 184. Smula, Västergötland, Sweden (now Dagsnäs, Bjärka).

Vg 197. Dalums, Västergötland, Sweden.

Västmanland, Sweden

Vs 1. Rytterns, Västmanland, Sweden.

Vs Fv1988;36. Jädra, Västmanland, Sweden.

Östergötland, Sweden

Ög 8. Västra Stenby, Östergötland, Sweden.

Ög 30. Skjorstad, Östergötland, Sweden.

Öland, Sweden

Öl 28 (58). Gårdby, Öland, Sweden.

Sources

Elena A. Melʹnikova. 2016. A New Runic Inscription from Hagia Sophia Cathedral in Istanbul. Futhark, International Journal of Runic Studies. 2016:7

Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine. encyclopediaofukraine.com

John Lind, Pauline Asingh, Lars Grundvad, Mahir Hrnjíc, Søren M. Sindbæk & Tonicha Upham and others. 2022. Rus — Vikings in the East.

Larsson, Mats G. 1989. Nyfunna runor i Hagia Sofia. Fornvännen 84

The Scandinavian Runic-text Data Base.

Svärdström, Elisabeth. 1970. Runorna i Hagia Sofia. Fornvännen 65.

Sveriges runinskrifter.